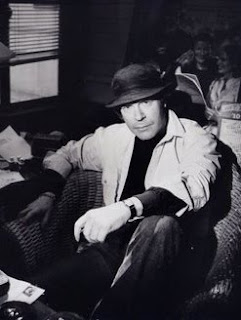

Okay, so not so much of a fairy-tale. My apologies for the botched conceit. Nevertheless, the truth of the matter at hand is still in there. The Kem, this so-called well-oiled machine, really did turn the world of film editing on its ear when filmmakers began using it in the late 1960's in larger and larger volume. The Kem one-upped the Moviola, more or less trumping all other editing methods with the facility of its use—and when computer software became increasingly sophisticated, the well-oiled machine that was once so super-sophisticated went the way of the dodo. Despite this, there were still those who remained admirably committed, contriving to hang on for as long as they feasibly could. One of these filmmakers, and perhaps the last one to completely let go, is the one who many cineastes would call the independent’s independent, writer-director Henry Jaglom, who is very much like a well-oiled machine himself (considering the fact that he is working on five projects simultaneously).

Prodigious and prolific are two words that leap to mind when you consider Henry, and these are two of the qualities I personally admire most about him. He is currently hard at work promoting his latest release Irene in Time, editing his upcoming film Queen of the Lot (a sequel to 2006’s Hollywood Dreams), producing and seeing to the editing of the filmed version of his play Always But Not Forever (adapted from his 1985 film), writing and re-writing a new play entitled Just 45 Minutes from Broadway and planning to shoot his next feature film. Each of these projects star actress Tanna Frederick, who made her debut in his Hollywood Dreams.

I had the privilege of meeting and getting to know Henry personally in 2006 and, even prior to that, we had been e-mail pen pals (beginning in 2004-ish), writing back and forth about films old, new, domestic, foreign, you name it…and, of course, about filmmaking as well. We have continued our correspondence and have known each other for these years now. In the summer of 2008, I was given the unique opportunity in being invited into Henry’s editing room to watch him work on his latest film. Immediately, what struck me as I entered the editing room was, “Okay, where ya hidin’ the computer here, Henry?” Even though I was aware he still edited on a flatbed, it didn’t really hit me until I walked into an editing room furnished with several celluloid-filled bins and, of course, the well-oiled Kem, complete with pieces of memorabilia hanging on the wall. He switched on his 8-plate Kem and started working diligently on the ending of his film. For a reasonable portion of the day, I watched him physically splice, cut, paste, wind, rewind and do all manner of things to his 35mm film elements—in a sense, watching both well-oiled machines at work. He would present me his guest, and his assistant editor Simone Boudriot with options and versions of the ending, only to, like a brim-hatted jack-rabbit, reposition those elements yet again in an almost lightning-fast way to present us with another version. This was a true sight to see.

Once a close personal friend of Orson Welles, and the last one to hear from him the night before the morning the movie legend died, Henry has carved a more than respectable existence for himself being the independent’s independent. He has never willfully directed a film for the studio system and helms films made his way and his way only. His distribution process is another fascinating aspect of his operation, also running like a well-oiled machine—all in all, a practical (and inspirational) business model for independent filmmaking. His company, Rainbow International Releasing, distributes the Monty Python films here in the United States.

Henry with co-editor Ron Vignone, photo credit: Tanna Frederick

The Jaglom way of working is a very singular way of working in that, ostensibly much the way Cassavetes made films, everything is written in detail beforehand and then, when shooting, the actors will take the reins and fulfill the intentions of the written scenes without adhering so strictly to anything written prior. He then, alone as writer, director and editor, finds the film in the editing room. It was with this knowledge that I was curious to see how Henry coped with having to switch to editing on a computer after decades of working on a flatbed and being initially resistant to the prospect of working any other way. Also, for the first time ever, he is working on Final Cut Pro not just with himself but also with a co-editor, filmmaker Ron Vignone (director of Say I Do and the upcoming documentary The Back Nine).

When I asked Vignone recently how Henry was enjoying working for the first time on Final Cut Pro, his response was simply, "Dan, he's loving it! He's having a blast!" Needless to say, I was quite surprised and started asking Ron more questions. So, eventually, I decided to schedule an interview with Henry to explore this subject. I found myself quite curious to hear what he had to say about the digital revolution and how it has affected his workflow as someone long-acclimated to a certain way of working.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

DK: Let’s start simple and point-blank. It would seem you’ve been resistant to personally using computer editing systems since their inception. What ultimately led to the decision to change over?

HJ: You know, I remember when I was in London shooting Déjà Vu, [Monty Python alumnus] Terry Jones took me in to edit something with him. He showed me how computer editing was done and assured me that I'd love it. My feeling then was that I never would, because I couldn't learn the technology and would somehow miss my whole laborious process—and I am amazed in working with Ron Vignone to say that this is not at all the case. Watching Ron edit a movie version of what he filmed of my play Always But Not Forever was really revelatory. I know it wouldn't have worked without someone who can do it as amazingly well as Ron can, who is wonderfully skilled and inventive and who has very similar tastes to my own, which is easy for me. And you know personally how difficult I can be on occasion and to be around all the time, particularly in the editing room. Ron is quite simply, really brilliant as an editor, yet open to my needs and my specific, idiosyncratic creative energy. So far I haven't been tempted to edit a single thing on my own though I had an important and complex dinner scene transferred to 35mm so that I could work on it while he was doing other stuff yet haven't ever sat down at my editing table where the spools are still left on it to do a single cut myself. I thought this would be a big adjustment, but it really wasn’t. I now wish I had actually listened to Terry Jones back in — what was it — '95 maybe.

DK: Can you talk about having been among the first filmmakers to have used the Kem for editing?

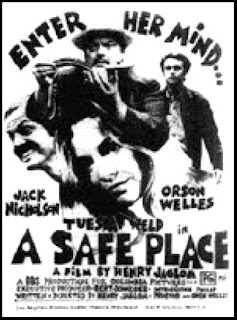

HJ: Orson absolutely insisted that I use it. He told me then that editors would resist the Kem because it was so simple to use that filmmakers would learn how to do it themselves and would not want the editors to come in and edit in their place, and he was right. He always said, and I agree, that filmmakers and directors should edit their films themselves. You really and truly gain an intimacy with the material that you almost always lose when someone else comes in to do it in your place. To me, it's like a painter calling someone in and telling him what colors to use on the canvas. In 1971, on my first film, when the editor assigned to me by BBS Productions for my film A Safe Place [with Tuesday Weld, Jack Nicholson and Orson Welles] fell asleep one day under some drug influence, I took over and found that I really loved editing and that it was essential for me, and no one else, to do it in the future.

DK: So this guy who they hired to edit really fell asleep under the influence while at the actual editing table? Doesn’t sound like a very productive working relationship.

DK: So this guy who they hired to edit really fell asleep under the influence while at the actual editing table? Doesn’t sound like a very productive working relationship. HJ: I remember his name was Howard Awk or Alk, he was famous at the time in certain hip circles for having made or edited a film with Bob Dylan. He was a friend of Dylan's, a graduate of the Second City and had been hired by Bert, from whom I had gotten the Kem. He got high, it seemed, a lot. So it was just when this guy fell asleep at the Kem a couple of times that I decided that he was no-go, and then somehow I convinced Bert [Schneider] to let edit it myself, and so I hand-edited my next—what was it?—14 or 15 films.

And it seemed to me that, with my way of working and not having each scene shot over and over again with different coverage and different angles and whatnot, and with so much improvisation, no one else could possibly put it together except me. In all reality, I write my films in the editing room. I always go into a project with a script, but it is never ever used verbatim, so the actors fulfill the intentions of the written scene without my imposing any rigid directions on them. Then, later in the editing room, I in a sense rewrite the scene with the emotional reality that the actors give me. So with that in mind, the fact that I am finding the movie in the editing process is the reason that I was the only one who could edit my films.

DK: I agree. It is your process, and that's just it.

HJ: I also remember when I was directing A Safe Place, we were shooting a scene and I was telling them what shot I wanted, and everyone in the camera department and continuity kept on telling me, "You can't do that! It's not gonna cut!" And I kept trying to convince them that it would, and it got to the point where I became so frustrated, I went over to Orson, kvetched a bit and asked his advice. He told me, "Tell them it's a dream sequence." At first, I was confused because it wasn't a dream sequence, but he told me that if you told people you were shooting a dream sequence, they would put aside any resistance towards your wishes and that they would do whatever you want. So I went back and told the cameraman that it was a dream sequence we were shooting, and he told me, "Well, why didn't you say so? I can put the camera over here and do all kinds of crazy things." [laughing] So, basically, no one else could see the vision I had for the edited product, so that was just more evidence that I was the only one who could do it.

DK: You’re working very closely with a co-editor, Ron Vignone, for the first time. How would you describe that working dynamic, considering the fact that you edited your own films by yourself from the beginning of your career?

HJ: It’s been easy and terrific! Ron knows all my work and my taste so well. He was always at my side during the writing of Queen of the Lot and during the whole shooting of it as well. Seeing Ron do what he did on Always convinced me to try this new system out, and working with him on that scene at the end of Irene in Time further convinced me, and now I am completely sold and spoiled, letting him do all the complex first roughs while I finish re-writes on my new play and work on my Jewish history book. If it weren't for Ron, I'd be sitting at my Kem for endless hours, going over to the shelves to take out reel after endless reel, putting each one on my flatbed and looking, cutting, rewinding, looking, cutting, rewinding, looking, cutting...for hundreds of hours.

DK: What have you learned about yourself and about your process as a result of this shift, and your adoption of using new filmmaking technology, if anything? Have you also learned anything about your process from working with a co-editor for the first time? Did anything surprise you?

HJ: I really haven’t learned much directly as a result of the change of process. I was definitely quite surprised at how much faster it is, and how much easier.

DK: I recall years ago now how you marveled at watching a two-minute short film of mine online, and your telling me how lucky I was to be coming of age as a filmmaker in the age of the Internet, when distribution was easy and turnaround time was so fast. Do you wish that you yourself had come of age as a filmmaker during the digital filmmaking revolution considering its advantages in the realm of production and distribution?

HJ: No, not at all. I like everything having been exactly as it was, and I've never wished retroactively for things to have been different. That is science fiction and it doesn't interest me, nor do I find it constructive to think about how things could have been different, because each film I have made is a perfect representation of who I was at the time it was made. So how could I possibly want it to be any other way?

DK: On a very general basis, what do you think of the phenomenon—that Joe Schmo from Oatmeal, Nebraska can access a digital camera very easily, pick it up and make a film on his own with very little resources and very little money? The digital revolution has furthered opened the door to regional filmmaking, which excites me as a filmmaker. However, do you think this new accessibility has opened the flood-gates for products of a decidedly lesser quality? How does that make you feel as a filmmaker?

DK: On a very general basis, what do you think of the phenomenon—that Joe Schmo from Oatmeal, Nebraska can access a digital camera very easily, pick it up and make a film on his own with very little resources and very little money? The digital revolution has furthered opened the door to regional filmmaking, which excites me as a filmmaker. However, do you think this new accessibility has opened the flood-gates for products of a decidedly lesser quality? How does that make you feel as a filmmaker?HJ: I am happy for everyone who now gets a chance who wouldn't have in the past. I think this is really and truly great. It’s the best thing that could have happened, and I am not really at all concerned with a perceived loss of collective quality of work.

DK: Were you initially amazed at the immediate results inherent in computer editing (e.g. that you can color correct without going to a chemical color-timer or that you can fade, mix audio, dissolve or superimpose titles onto images without optical printing)? Were there any other surprising revelations that you discovered when you chose to adapt to the new technology?

HJ: No real surprise there. I did know all this, but who doesn’t know this? It’s so out there now, it seems like. That's what is so amazing!

DK: Considering the way you work and your artistic process, have you found it easier or more difficult to edit improvised scenes with the new system?

HJ: Both really. I remember Orson watching me edit improvisational acting one day when I was putting together Can She Bake a Cherry Pie?, him sitting behind me and smoking his Monte Cristo and being utterly fascinated as I made it up as I went along, amazed when I took a bit of someone's dialogue out of one mouth and put it in another, or taking just syllables here and words there and as a result re-writing whole scenes, changing whole sentences and making several actors look as if they were saying things that they never actually said. But I am enjoying watching Ron edit the scenes and then showing it to me and then working on it with him, and so on, like I guess more traditional directors do, and the speed with which all this can be done amazes and delights me, what would have taken me weeks can be done in one sitting. It's liberating.

DK: To quote your mentor Orson Welles, “I believe it is possible to spoil a young filmmaker with too much privilege, too much money and too much comfort so that he does not learn one of the main arts of directing, which is the ability to walk away from something.” Do you think that it is in turn possible to spoil young filmmakers with the advantages of the digital format?

HJ: I don't know where you got this quote, but Orson said thousands of things, whatever came to his mind at the moment he said, and never seriously thought about this. Don't take what you read seriously, people say all sorts of things. And I don't believe something like this can spoil a young filmmaker. Quite the contrary, it opens up the form for people. I have always encouraged the growth of digital filmmaking for all it allows young and beginning filmmakers, but have just never been interested in working within it myself, until now.

DK: I know a few people who feel that way, that computer editing spoils you to the point where you can't think and consider fully what you're doing because it is so fast that you want to do it and the next minute, it's done...no extended thought process that one would get from winding, cutting, splicing, watching.

HJ: I do understand what you're saying. I just think that the more open the medium and the form is, the more interesting the results are ultimately going to be.

DK: In any case, do you see your beginning to use editing software as a gateway for you to in the future shoot digitally on HD, or are you faithfully committed in sickness or health to shooting in 35mm?

DK: In any case, do you see your beginning to use editing software as a gateway for you to in the future shoot digitally on HD, or are you faithfully committed in sickness or health to shooting in 35mm?HJ: I really have no commitment to anything like that now. But who knows? It could go either way, I don't know yet. At various points throughout my editing process, I screen the films in rough cut form. I would always have to take the work-print to the lab and get it transferred at various stages to a DVD. Another perk is that this new process cuts down on that expense as well, and you can make DVDs at various points without that hassle. So the more I am seeing the various perks of doing things digitally, the more I become open to further changes.

DK: Does 35mm editing still have any advantages over digital editing?

HJ: One thing I can say is that I no longer feel like an artisan, like I used to—the feeling of what it is to work with your hands. One of the best things about working in film on a Kem and on any flatbed is feeling the film between your fingers on the editing table and watching light pass through the actual elements when you’re editing. There’s just nothing like it. So, if there is anything I miss, it is that. I am not so sure you can feel anything even akin to that when you edit on a computer. It's just very different.

DK: On a lighter note, I remember you saying that you intended to make a film for every letter of the alphabet (i.e. A for Always But Not Forever, B for Babyfever, C for Can She Bake a Cherry Pie? , D for Déjà Vu, E for Eating, F for Festival in Cannes, etc). Is this still a goal and do you think the quickness of computer editing can facilitate that goal?

DK: On a lighter note, I remember you saying that you intended to make a film for every letter of the alphabet (i.e. A for Always But Not Forever, B for Babyfever, C for Can She Bake a Cherry Pie? , D for Déjà Vu, E for Eating, F for Festival in Cannes, etc). Is this still a goal and do you think the quickness of computer editing can facilitate that goal?HJ: [laughing] Yes, it’s still a goal…if I live long enough to see to it. Editing on a computer is quick, so we shall see.

DK: A great teacher of mine once said, “If one studies history, one should begin at the beginning. Therefore, filmmakers just starting out should learn how to shoot on film elements before moving onto video in order to understand the roots of filmmaking.” Do you think fledgling filmmakers should first, or at some point, learn how to shoot and edit on film with a flatbed to understand from hence and whence we came?

HJ: There are no rules, and I believe anyone who preaches rules is missing something really valuable. Everyone is different and should approach making films in any way he or she thinks is best, most importantly no one should listen to anyone else who tells them that there is a right and wrong way to do things....just do them and don’t let anyone tell you that you can’t. That is the best advice I can give...to not let anyone tell you, "No, you can't." And the digital age makes that more possible for people, in my belief. I've made a career out of telling people, "Yes I can!" If I can make that "Yes I can" happen from editing on 35mm, they can make it happen with the new ways made available!

IRENE IN TIME is playing at Laemmle's Sunset 5 Theater in Los Angeles. Henry's play JUST 45 MINUTES FROM BROADWAY premieres at Edgemar Center on October 1.

No comments:

Post a Comment