I became a biographer by accident. You might say I sort of fell into it, despite having been a film writer before embarking on my book Sidney J. Furie: Life and Films. I spent years voraciously binging on show-business biographies, through which my “stomach” for anecdotes swelled. As I got gordo on such trivia, I eagerly regurgitated this steady diet of behind-the-scenes stories at will, for whomever seemed even marginally interested, sometimes even in the presence of perfect strangers. (I could have said that my mental “library” for stories grew so overstocked that it had to outsource, but I found the dietary metaphor funnier and more apropos.)

Galvanized by the fact that I myself would need to spring into action if I wanted a book to exist on one of my filmmaking heroes – a slightly more esoteric name than the type of directors who traditionally get such coverage – I underwent a kind of baptism by fire. The book became an addiction, a passion, a quest, a crusade. I’m deliberately using very dramatic words, but they are very real to me, as is the project very near and dear to me.

I had written many articles and casual pieces about film, but had never undertaken such an epic endeavor as writing a book about film. The icing on the “cake” was, bar none, getting to know my subject as a human being and, ultimately, as a friend. By the time I delivered my full manuscript to my publisher in the summer of 2014, a strong sense of post-partum depression swept over me. Even though at that point I had lots of rigorous editing to anticipate, I wanted to do it all over again, to start again from scratch, like a child who shouts “Again!” after whirling down a water slide. I wanted to re-experience the eureka moments of finding the research materials that magically dissolved question marks – make no mistake, for any scholar or researcher, this is a drug. I wanted to re-interview Sidney’s stars and collaborators. I wanted to take those long, recorded walks with Sidney all over again. My overall involvement with the project taught my endorphins how to dance.

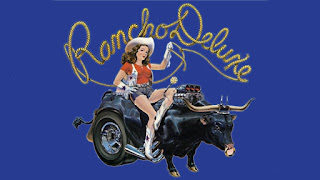

Since this was wishful fantasy, I had no choice to move on. I still resolved to do it all again, this time with a new subject – and, as it turns out, a new publisher. The first subject I considered as a follow-up was Frank Perry, director of David and Lisa (1962), The Swimmer (1968), Last Summer (1969), Diary of a Mad Housewife (1970), Play It As It Lays (1972), Rancho Deluxe (1975), the now “infamous” Mommie Dearest (1981), and a number of notable others. I was drawn to Perry as an early independent filmmaking pioneer, as someone with a specific and refined sensibility, and as a deft director of performance who amplified his actors’ contributions with exquisite staging and camerawork. Beyond that, his films were explicitly philosophical in nature, but nevertheless still managed to emotionally involve their audiences. Thus is the particular nature of Frank Perry’s refinement: they are exercises for the heart as much as for the head.

Deciding to just dive headfirst and right into it, I contacted filmmaker friend Henry Jaglom, asking him to put me in touch with the Perry collaborators I knew that he knew. This indeed proved fortuitous, although it certainly did not seem so at first. His response: “Sorry, Dan, I know someone working on a Frank Perry book.” Considering that Perry had rather fallen into obscurity, especially in the years since his premature death to prostate cancer (Perry's 1992 documentary On the Bridge follows him in treatment battling the cancer), I was flabbergasted. “How could that be?” I asked myself. Maybe Henry misheard or confused Perry for someone else, I first told myself. “No,” I said, “Henry’s definitely not the type to confuse directors.” When I chanced to meet Joan Micklin Silver, a filmmaker I’ve admired since childhood (I saw her masterpiece Chilly Scenes of Winter at a very young age), it seemed to be in the stars. After convincing her to work with me on a book, I sped forth on that project.

It wasn’t until this past summer that I discovered the name of my fellow Perry admirer. Enter Justin Bozung, a freelance film writer, blogger, researcher and part-time archivist, who has been working on his Perry book for the last two years, while also working on a book about the films of Norman Mailer. A bittersweet sigh: “Good,” I said to myself. “While he’s covering this never-before-covered filmmaker, I can do another filmmaker of that stripe. We’re both working for a common cause: redirecting the spotlight towards lesser known directors who deserve it.” I’m always drawn to covering directors who haven’t been given proper coverage thus far, and breaking with the scholarship monopoly that benefits a certain untouchable pantheon of artists, so I'm thrilled that Justin is doing the same with Perry.

Gam zu l’tovah, so goes the old Jewish saying. In English, we’d know it as “everything for the best.” In Jewish culture, though, the deeper meaning is “everything for a reason.” Considering the fortuitous turn of events here, that has a wisdom. The fact that I contacted Henry first, before anyone else, and then to have Henry tell me about another author covering Perry, saved me wasted time and energy. Imagine had I worked for months only to meet Justin further down the pike! Oops. So, I thought I’d present an interview I conducted with Justin, discussing his process as a biographer, as well as challenges we as biographers face when taking on new subjects – and in our case, subjects that prove to be much harder sells than doing the 127th book on Hitchcock or Welles.

First, I offer the biographer’s biography: Justin Bozung is a freelance film writer, blogger, researcher and part-time archivist. He has researched and contributed to two books about Stanley Kubrick and has written for such print publications as: Shock Cinema, Videoscope, Bijou, Whoa, HorrorHound, Fangoria, and Paracinema magazines. He is on the board of the Norman Mailer Society, curates the Norman Mailer Podcast Project over at ProjectMailer.net, and works with the Norman Mailer Estate as a video/audio archivist. He is the official biographer of film-maker Frank Perry. His next book Film is Like Death: The Films of Norman Mailer will be published in mid-2016.

ConFluence-Film: So, we’re both drawn to Frank Perry’s work, but for you personally, what was it about Frank Perry that called for such a work-intensive showcase as a full book?

Justin Bozung: There are many reasons why I chose to start work on a biography on Frank Perry. I guess, originally, my motive was simply to just research and write a book about Frank because, as the fan of his work that I am, I was so disturbed at the lack of information out there about him and his films. There's been nothing written about Frank to date. Originally, I had envisioned this project as a dual biography, really. I wanted to write a biography about Frank, but also his first wife, Eleanor Perry. I wanted to write it as if it were a giant X, and I'd have them intersect in the middle and then continue on down their respective paths after their divorce in the film world.

CF: Yes, Eleanor was vital in the early part of Frank’s film career, and an interesting figure herself. In researching my Joan Micklin Silver book, Joan told me that she worked with Eleanor on a number of unproduced scripts in the late seventies, some time after she divorced Frank. Digging into Eleanor a bit, I discovered that she had done things like painting over the Cannes ad billboard for Fellini’s Roma because she thought the graphic was sexist and offensive.

JB: Neither Frank nor Eleanor would've had a career or made any movies if it had not been for the other's talents. It’s important to consider that. They really complimented each other when it came to the film business, although Eleanor, in the forties, while she was still living in Cleveland, had written a series of true crime novels with her husband, who was a prominent area lawyer. They wrote these books under the pen name, Oliver Weld Bayer. In 1945, a producer bought the rights to one of their novels, and made it into a film, Dangerous Partners, with Eleanor being tasked to write the screenplay. While Eleanor had this experience under her belt, by the time she had met Frank in New York in the late fifties, she had been hyper-focused on writing for the theater, which is where Frank and Eleanor met, though Frank, by that time, had no film experience. With Frank, though, as I've researched him, and talked to some of his family and friends, I've just made many personal connections in his life with which I have identified…things that I really don't want to go into here. Frank was very passionate about working with actors; in fact, he was one of the first non-actors to be granted membership into the Actors Studio in New York to study. He was passionate about actors, and he had a knack for working with them. And he had an incredible eye for discovering talent. He discovered Cathy Burns, and he more-or-less discovered Bruce Davison. He discovered Janet Margolin to the extent that she had been known as a theater actress and not a film actress before David and Lisa (1962). Frank brought many actors to the front, who still credit him for giving them their first big break.

JB: Right! Another aspect of Frank's career that drew me in was that almost all of his work was with great novelists. He also had this incredible knack for convincing writers to allow him to adapt their works. In that way, he was a hustler. What's not to admire about that? He worked with some of the greatest literary minds of the twentieth century: Joan Didion, John Cheever, Truman Capote, etc...the list goes on and on. And that doesn't include the writers he was working with on films that he couldn't get off the ground, with amazing writers like Patricia Nell Warren and Walker Percy, for example. He had a knack for a great story, and not just a great story, but one that was really ahead of its time in terms of subject matter and point-of-view. He was very literary-minded, and I really like that about his work. Also, it really bugs me how Frank isn't quite as well-known as he should be today. Things are slowly coming around, but his legacy should be farther along than it is by now, in my opinion. So I'd like to help his family achieve that too. There's this idea, as well, that Frank's films post-divorce from Eleanor aren't as "good" as those that he made with her, and I would disagree with that notion. So, my job, really, is to sort of debunk a lot of things out there concerning his life and his films. I care about his work and his legacy, that's probably because, as I've gotten deeper into researching him, I have discovered these aspects of his life that we share between us. How we were both raised, traumas, etc.

CF: Was it easy getting the okay from the Perry estate, and were you granted immediate access to Perry's papers and archives?

JB: It was pretty easy. The challenge, of course, came in finding out who was in charge of the Perry Estate and who controlled what aspects, and all that. Frank was married three times, so there is some red tape there concerning who owns what and who is charge of what. Frank's archive with his papers sits at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. But they are currently private holdings there; which means that not just anyone can go into them to research Frank. You have to get permission from Frank's estate directly to enter, and to date, I've been the only person allowed into Frank's papers outside of any Wesleyan students who are in the film program there. Frank's papers will likely be made open to the public, but probably not until after my book is complete.

CF: Establishing trust with your subject -and/or- his/her family is crucial. I've spoken with a few other biographers about this, including Foster Hirsch, in relation to his Otto Preminger book. And Nick Dawson too, with his Hal Ashby book. Sidney Furie didn't want to know hide nor hair about any book, because he distrusts journalists...and hates walking down memory lane even more. It wasn’t until he discovered I made films myself that he finally agreed, because he loves talking shop with fellow makers – and eventually, we became best buds. It’s one of the greatest gifts I’ve ever gotten. Joan Micklin Silver, ditto. How was that for you, and what tips would you personally give other authors in going about doing this?

JB: Well, as I mentioned, originally I wanted to do a dual biography about Frank and Eleanor Perry. That went by the wayside when I exchanged a couple emails with Eleanor's son, who today, is a pretty well-known writer. He was really cold on the idea of a book about Frank and Eleanor, in fact, he even suggested that their work wasn't even important to film history.

CF: That's just so absurd to me.

JB: Yeah. So, with no support from Eleanor's family, that left me to focus on Frank, which is disappointing to me, as I had wanted Eleanor to have a major role in the book, now she's barely there on the page. It isn't right, because she did have a major role in those early films. I mean, she wrote them! Frank and Eleanor's divorced in 1971, even though they sort of stayed friendly, made her slightly bitter over how it all turned out.

Frank went on to make more films, and Eleanor was alienated as a female screenwriter in Hollywood. She was profilic with projects that went into purgatory or turn around in Hollywood. She wanted to direct. She was slated to direct a western: The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing (1973), but in the end she was screwed over on that, and the script was re-hashed by another writer after she was fired over conflicts with the producer of the film. In the end she was bitter about how Hollywood treated her, and so much so that she wrote a book about her relationship with Frank at the end of the seventies which also took big stabs at Hollywood and the treatment of the screenwriter, in particular, the female screenwriter. And the book really hurt Frank's feelings to boot! So I think her son's lack of interest in wanting a book written about his mom really has more to do with his concern about not wanting old wounds opened up.

With Frank's estate, they were sort of on the fence at first, but not because they didn't feel the same way about Frank's legacy as I did – only because they didn't know who I was, or where I came from. So it took a few phone calls and some discussions about Frank and his work with his longtime personal assistant turned producer, his ex-wife and her son – who are both executors of his estate. We talked about Frank and his films and why I felt compelled to write the book in the first place. Who would publish it? When would it be done? What would my focus be? Would I dish any dirt? They asked to see previous work that I had done too. I sent them magazine articles and interviews that I had written and done prior. I sent them a manuscript for a book about Kubrick's The Shining that I had just finished working on at the time. Once we had talked a few times, and they had read my previous work, they felt comfortable in giving me permission to access his papers and they decided to help on the project in any way that I asked them to.

CF: What are the most valuable resource you've had at your disposal so far?

JB: Never trust a writer who doesn't use the library.

CF: Absolutely! I must have spent weeks at AMPAS's Margaret Herrick Library alone, not to mention the pertinent university and institutional libraries!

JB: And writers shouldn't forget to access the obvious too! Look on websites like eBay for materials or on iOffer. It doesn't happen every day, but on some days, you'll be lucky and find a weird, obscure magazine that was only published for a handful of years that may feature an interview with your subject that you didn't even now about prior in your research. Cross-check bibliographies at your library, and then hunt down missing magazine articles on sites like Abebooks or Alibris. I've found actual scripts to Frank's films online for sale---scripts that aren't even available in Frank's archives at Wesleyan. When hunting for scripts use Scriptfly or Scriptcity in Los Angeles. If you find a script that you need for your project, one that will aid you in your research, you can buy it, and in 24-hours they'll email you it in PDF or they'll ship you hard copy. Use the Internet, but at the same time don't limit your research to the internet exclusively. If you do, you will fail. There is a wealth of information out there online, but it needs to be cross-checked and verified.

There are huge errors of information out there, particularly concerning Frank Perry's films. One of the biggest errors out there concerning Frank Perry is that his film Last Summer (1969) was released with a X-rating and then re-cut later on and re-released into theaters with an R rating. This is something that is mentioned on Wikipedia online, and in books that have mentioned the film in the past. This is simply, not true. I'd rather not say now why and how this isn't true, but it will be clarified in my book about Frank when it comes out. This is, of course, just an example. There are certainly errors in print too, but I go by the addage that if you hear something once from someone--it's just a rumor. If you hear the same thing from several people, it's most likely truth. The danger is when the rumor is printed too many times, effectively making it a truth to many. I'm trying not to let that happen per Frank Perry.

CF: Yes, I’ve encountered a great deal of apocryphal information about Sidney and Joan in researching my own books. The most hysterical one, one that sent Sidney up in stitches, was that Charles Eastman wound up directing the rest of Little Fauss and Big Halsy after Sidney left the production. In the first place, Sidney never left the production, nor was the shooting ever at any point tumultuous, let alone to the extent that anyone would have walked off. In the second place, Sidney only met Eastman once, in producer Al Ruddy’s office, with two bull mastiff dogs. He was a hands-off writer and, once turning in his script, never was heard from again on that production. So, nonsense in print, for sure. Then there was one I read that Michael Caine visited the set of The Appaloosa, where Brando told him that Sidney couldn’t even direct traffic. From Michael Caine’s lips: “That’s a load of rubbish. I was never on that set even for a second.” But of course this gets printed in a book and it has a deleterious affect on public perception, and then make way for the nonsense stories getting reprinted. Part of our job is often to debunk myths that are comprised of sexy, "juicy" but fundamentally untrue stories.

JB: Yes, that happens more than people know. Frank's archive at Wesleyan has certainly gifted me with a lot of information I need for my book on him, but there are huge gaps in his chronology as well. So, it has been very important to me to get out there and talk to as many people as I can concerning Frank and his work. I've done over 150 hours of interviews in relationship to the book project to date, and I anticipate to double that time before its all said and done. I don't think one can write a book in under three years, at least, a book that I'd ever take seriously. So the interviews are extremely important, if not, even more important than my access to Frank's archive. There is just too much to be explored, and as with everything I try to do, personally, I want my work to represent something of a definitive nature regarding the topic. I find that setting out to "leave no stone unturned" will only leave stones unturned. When I'm researching something--when I feel as if I've cracked the "case," I stop and take a break for a couple weeks. I start looking at something else, because, at a point, your mind tires and you need to re-set, it becomes difficult to see everything. It never fails me. Once you've taken the break and then return to your subject, you will always find things that you missed the first time around.

CF: Yes, on the Furie book, I had the privilege of jumping between writing the book and also prepping, shooting and then editing my feature film Raise Your Kids on Seltzer, which likewise took years to reach completion. I've accounted to many people how that rhythm helped clear my head, on not just the one project, but both projects. It's a routine I hope to maintain: balancing the writing of a book with the making of a film.

JB: And, plus, it's always interesting to see how things you experience in that break alter your perception of your subject later on as you're following up on them in the second round of research or study.

CF: Absolutely! Now, you and I both agree that Perry isn't nearly as well-known or admired as he should be by cineastes, scholars, and cinephiles. Like my own subjects Furie and Silver, Perry is either ignored or forgotten, despite his strides as a relatively powerful, prodigious independent producer-director. What specifically has challenged you in the writing and research process so far, with this in mind?

JB: I don't know if I've experienced any challenges regarding Frank's work. I love everything about Frank's work. There isn't a "bad" film in the lot. I've always been a firm believer in not reading or paying attention to what a critic has to say about any filmmaker or a film itself. Film as an art form is completely subjective, therefore, the notion of any criticism pertaining to any film is completely null and void of meaning or matter. I don't like thinking negatively about anything, really. I prefer to think positively and objectively in life, and that carries over, for me, into my thoughts or theories about art itself. You know, one of my favorite film writers, or scholars – whichever you'd perfer to call him – is Rudolph Arneheim. Arneheim crafted a very potent metaphor for thought back in the 1930's while he was at Harvard about perspective pertaining to the arts. He said, and I'm totally paraphrasing here: "If you see a box on a table, if you look at that box while standing in front of it, it's just a box. But if you walk around the box, turn the box to a different angle, alter the box in some way, then the box becomes something else altogether." That's kind of how I approach film and art. I don't think it's the job of the the filmmaker to show me the greatness of their work. I think it's up to me to find that greatness in their work myself. I don't think that films were intended to be viewed only once, which is often times what critics and these mass-consumer new cinephiles do.

There are no such things as bad filmmakers or bad films. Of course, I have the same post-modernist programming that most of us have. There are times when I watch a film, and I may not always enjoy it, but it’s in those moments that I realize that it's not important what I thought about the film, its my job only to find something in the film that is great, as a film lover. In those moments, you'll always discover something of merit that will re-set your mind and allow you see things in a completely different light pertaining to that particular work of art, or in this case, the work of a filmmaker.

CF: I wish I could be like that, but alas, I can be fairly tempestuous when it comes to my "problem" films and filmmakers, but that's actually just the filmmaker in me coming out...always the "backseat driver" thing. It's a curse that a few of my filmmaker friends have as well.

JB: With Frank, I'm still working on the project. I'm only still working on the book because I took twelve months off because of a legal problem concerning my use of materials from the archive in my book. I decided that if I couldn't use anything from his archive, then I wasn't going to do the book on him in the first place. But that's been cleared up now, and it took all this time to straighten it out really. In that time away, I took an opportunity to work on another book project, a book about Norman Mailer's films that will be out next year through a major publisher. With Frank, there are, as I said, huge gaps in his story that I haven't even been able to put those together just yet. The parts of the book that are done or about done, thus far, are sections where I've got a wealth information pertaining to certain films in his oeuvre. I mean, I've got huge gaps pertaining to Ladybug, Ladybug (1963) because many of the actors from the film are either dead, were one-time child actors and not current in the business, or are not interested in talking about the film because it was such a flop for United Artists and/or are writing memoirs that talk about the making of the film, like actor William Daniels. I still have lots of gaps pertaining to his teen years, his time in the military, his time at college, and a couple other films as well.

CF: I quite like Ladybug Ladybug. I saw it for the first time last year and couldn’t understand why critics shot it down. It's a lovely piece of work, beautifully made and, in my opinion, one of the best nuclear scare films of the era. What are you favorite Perry films?

JB: I'm partial to Last Summer and Play It As it Lays (1972).

CF: I’m a really big fan of Play It As It Lays! I always thought it would make a brilliant, ideal double feature with Jerry Schatzberg’s masterpiece Puzzle of a Downfall Child (1970).

JB: And I love David and Lisa. David and Lisa doesn't get the respect it should. It was one of the first independently-made films to be nominated for an Academy Award, and it deserves respect and awe for where it fits into the historical landscape of American independent film. I mean its right up there as far as earlier indies go with Shadows (1959). I love Compromising Positions (1985). I love all of his work though. I'm even wowed by his epic three-hour TV pilot Skag (1980), which starred Karl Malden and Piper Laurie.

CF: Yes, we discussed Compromising Positions one-on-one some time back. I admire that one greatly, and feel it is criminally underrated and unjustly forgotten. It's a perfect and quite apt companion to the earlier Diary of a Mad Housewife, complete with the odious Edward Herrmann character, the officially "out to lunch" husband. Are there any Perry films you champion that might have bombed with critics and audiences on initial release, but deserve a second look?

JB: Again, I like them all. I don't think there is a "bad" film in the lot. Certainly, certain Perry films have their detractors. Certainly, Compromising Positions is one that not a lot of people like, even though when it was released, it did well with the critics, and was used to suggest that Frank was sort of "returning to form" or back on his "game" after coming off of a couple TV movies. I think its a bit ahead of its time. It's certainly a revisionist take on the detective genre, even though it apes classic film noir visually in certain moments. Also it has a pre-Desperate Housewives kind of thing going on in it. It tackles the second-wave of Women's Lib that came in late seventies and early eighties. I do like Hello Again (1987) as well. If there is one Frank Perry film that everyone seems to think is a stinker it would be that one. I think it's really quirky and funny. At its core, it really is a Bride of Frankenstein meets the screwball comedy from the '30s. Can't you just image someone like Katharine Hepburn in that Shelley Long role? Or a Lucille Ball? Frank even references Bride of Frankenstein in the visuals of Hello Again. Watch for that great shot of Shelley Long after her sister "Zelda" has brought her back from the grave in the cemetery. She's dressed in that long, all-white dress and white elbow gloves. She's framed identically as to how James Whale framed Elsa Lanchester as The Bride after she's just been created and unveiled for the first time on screen. It really is a goofy screwball comedy.

It's almost something out of the Theater of the Absurd, which of course, was designed to produce comedies of manners that not just explore the human condition but the state of human relationships in contemporary sociological terms. Had Hello Again been released in black-and-white people would likely look upon the film differently. Again, it goes back to what Arneheim said about perspective. But there are many films like that.

CF: Yes, I never thought that Hello Again was nearly as “bad” as critics made it out to be, though it's certainly not a favorite Perry film for me. And your observation about Hepburn and Ball is really on-point. I’m a big fan of Rancho Deluxe. I find it one of the great unheralded films of the seventies.

JB: Yeah, with Hello Again, Disney/Touchstone really put their foot down on Frank during the shooting. It wasn't a good experience for him. Shelley certainly wasn't Frank's first choice for the film, but because she had ties at Disney, because she had made them money with Outrageous Fortune (1987), they insisted that Frank cast her in the lead role. In the end, Disney had too much input into the film itself, and into Susan Isaac's script, and Susan sort of gave in to their demands regarding the changes they were requesting. Susan's original script for Hello Again is hilarious. The film as it stands now, is also really hacked up from a editorial perspective as well. But, still, in its current state, it's a funny screwball comedy in the spirit of those classic Hollywood films of the '30s and '40s.

CF: Mommie Dearest? I would have been conflicted covering that film, if I had been the one to do the Frank Perry book. Would I or could I indulge the “so bad it’s good” crowd, who love it for its camp value, or would I forge my own path?

JB: Mommie Dearest is another of Frank's films that I feel really has been run under the bus. While, it's become this campy cult classic, I really don't see the film through that lens. I don't see Faye's performance as being over-the-top either.

CF: You’re not going to believe this, but I totally agree. From everything I’ve been led to understand about the real Joan Crawford, I can’t help but think that Faye Dunaway’s performance is pretty on-target, though I can still nonetheless totally understand why the camp crowd has a blast with it. But I think the acting and direction are pretty courageous and audacious in that film. I don't even call the scene with the wire hangers "the wire hanger scene." I refer to it in my own head as the Kabuki theater scene, considering Dunaway's face-cream makeup.

JB: Again, I think, it's a film that would've been better suited for black-and-white. There's something about color film that conflicts with American film audiences, whereas in a way, it portrays an attempt at reality, and when that reality is segmented or skewed, it really inflicts harm on how we understand that relationship to reality itself, as if a film in color is actually a version of reality. We remember films as if the stories happened to us personally in a way. And there are critics who argue that the film isn't faithful to the book by Christina Crawford as well. Truth be told, Frank Perry and Frank Yablans based their screenplay on not just the Crawford book, but on other sources as well. One book that they were big on was Conversations with Joan Crawford. That was a huge influence on their screenplay. I don't see what Faye Dunway did in that film as being anything different that what Joan Crawford was in something like Strait-Jacket (1964) for example. She was an actress with a Capital "A." Faye's performance is really amazing in the film. I think it's a brilliant film that has a ingenious structure from a narrative perspective, great performances, a lush, old Hollywood-sounding Henry Mancini score, and brilliant direction. Faye and Frank had a good relationship with each other too, certainly they have worked with each other before on 'Doc' (1971), another brilliant Perry film.

CF: Has anything truly interesting, noteworthy or unpredictable happened amid your investigation into Perry's life?

JB: I mean, isn't it all interesting? Certainly it's all noteworthy, and as in all life, rarely predictable. There are aspects to Frank's story that are shocking. Certainly, he earned no points during the Frank and Eleanor Perry divorce, certainly he had a history of not looking back, leaving people important to his life and the sucess of his films in the dust after he didn't need them anymore. His story is tragic on a few levels, awe-inspiring on others, because he was a go-getter. He was self-created. He was independent in the sense that he worked out of New York and that prevented studio interference on much of his work. But make no mistake, his pictures were financed by the studios. They are studio films, and in a weird way, made independently. His childhood was painful, his final years were painful and sad too. He left us too early certainly. One can revel in his guts and audacity as a filmmaker, and also one hopefully will feel a great empathy toward him after his story is completed by me. He was a big personality. That's something that no one really knows about him. Those that knew him well always remember, all these year later, after he's been gone, now for 20 years, as a big personality.

CF: Do you have ideas about how to promote the book considering the slightly more esoteric nature of the subject? I've had to contend a great deal myself with this.

JB: Not sure what to say about this. I suppose it's foolish of me to not care about this stuff. But I really don't. I know that doesn't answer your question. I guess it is a cliché for me to suggest that, but its how I feel. I don't work on my projects because I want to be famous or well-known. I don't work on my projects because I want to do anything except explore the subject as it satisfies my own desires for learning and knowledge. The book is almost secondary, really. In the end, I guess I'm really asking a question: What does it matter how you promote your book? What is the means or the goal in doing such? In this day and age, there are no publishing advances for writers. Unless you're a celebrity who is writing a tell-all, forget about it.

CF: Yes, I wrote my book on Sidney purely out of love. When it was released, the onus of promotion was thrust upon me, and my publisher encouraged that I get my hands dirty, which I gladly obliged. I definitely want people to read it, though, and desperately want audiences, new and old, to see the films covered in the book again, so I guess it’s a necessary evil. I’m pushing pushing pushing for people to pick it up, and hoping Sidney gets some mileage out of it. I’m 101% doing it for him more than anything. Sidney himself and his films are very important to me.

JB: Yes, my interest is in film, so be interested in film. If your work is any good, then it will find an audience. If not, who cares? It's not like you're going to retire a successful film book writer, right? Do you think Jonathan Rosenbaum is living in a lavish pad in Chicago counting his royalties from his film books? No, but he's one of the great film minds of the twentieth century. That's what Rosenbaum will be remembered for when he's gone some day. Write the book for you. Leave the marketing up to your publisher. If you're worried about marketing yourself, then you're probably working toward the wrong thing in the first place. Rudolph Arneheim probably wasn't concerned with being famous or selling books, so I don't think anyone else should be. At least, if you're a serious film person, that is.

CF: Thanks for taking the time to talk with ConFluence-Film Blog, Justin! I personally look forward to your Frank Perry book with great anticipation.

Justin also took time discuss the “art” of the interview:

“I've studied, quite a bit, the work of filmmaker/journalist/photographer Lawrence Schiller, who is probably the greatest interviewer in the history of the world. If you want to learn how to interview anyone, study his interview tactics and his overall body of work. He's a genius. I'm lucky enough to know him, as he and I are both involved in the Estate of Norman Mailer, and I've had the opportunity to interview him about interviewing people. When Larry Schiller tells you you're a good interviewer, you know you're on the right track!

“Interviewing someone, though – the key is to do your research. Don't wait to talk, don't be stuck in your questions. I've gone into interviews with no questions, and I've gone in with one hundred questions. The key is listening. Also, I try to establish some sort of personal connection with my interview subject prior to firing questions at them. I try to make them comfortable. I try to keep it conversational. I want it to be like two old friends talking together. Try to get a good idea of that person's mood in the first couple minutes of talking with them and adjust your approach based around that. Do the research, don't ask questions they've been asked a zillion times prior. Avoid clichéd questions. Read previous interviews with them, see where the previous interviewer faltered, and cover his tracks on your own. Also ask follow-ups to the questions that they were asked in previous interviews. I don't mind open-ended questions, but you need to be careful with them because often times you won't walk away with the answer you need or are looking for, so if you do choose to go in with open-ended questions, be prepared to ask specific follow-ups within their response. Don't be afraid to go after what you're trying to find out. Respect your subject, and don't waste your subjects time either. Keep it fun and respect their art. Know your topic too! Don't interview a first assistant director if you don't know what a first A.D. does on a film set! Respect their craft. Go after what you want, otherwise you won't get it. Don't ask questions you already know the answers too either. It's just a waste of time for all involved. Don't hog their time, be grateful that they agreed to talk with you in the first place, and never believe that you're entitled to their time either because you're sitting down with them, or have them on the phone.”