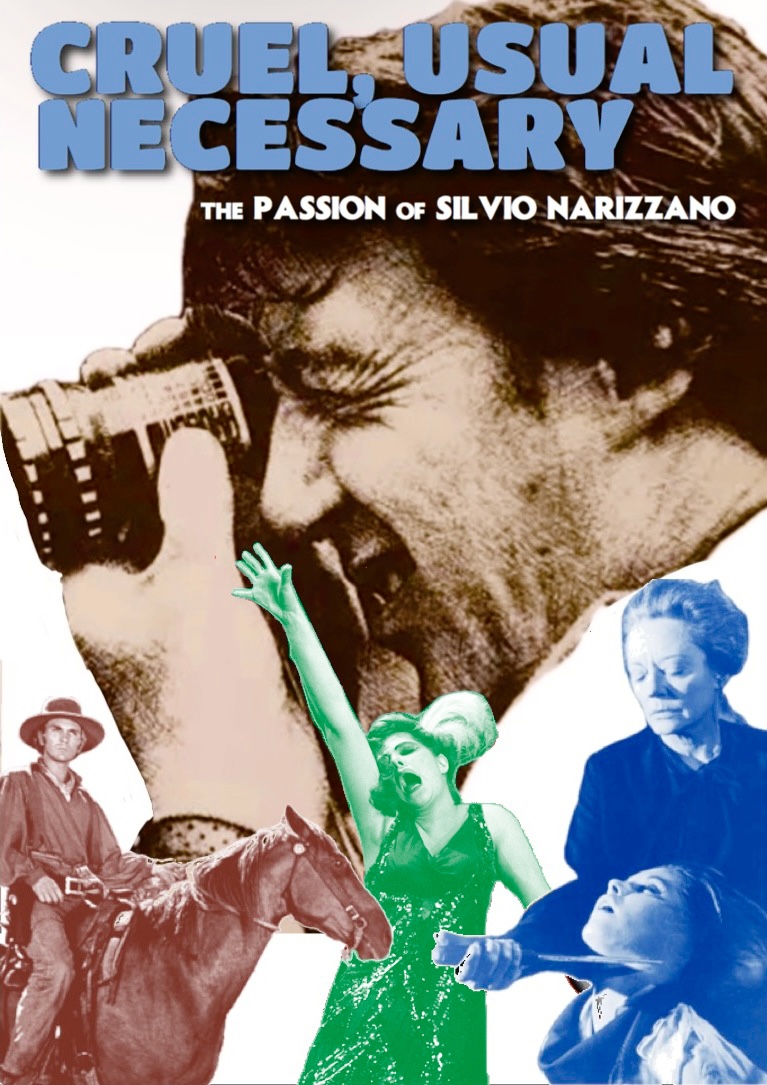

ConFluence-Film and Public Shore Films has entered a partnership with Via Vision's Imprint Films in Australia. Filmmaker Daniel Kremer was contracted to produce a series of video essays, essay films, and documentaries, most notably Cruel, Usual, Necessary: The Passion of Silvio Narizzano. He is following up the project with A World of Innocent Sinners: The Fables of Philip Leacock.

Filmmaker Daniel Kremer at Via Vision's Imprint Films

The Spaces Around Stories: The Films of Michael Glover Smith

There is a sequence at the center of Michael Glover Smith's Mercury in Retrograde (2017) that reminded me of something a rabbi once instructed me. I asked this rabbi to recount this pearl of Chasidic philosophy for the occasion. "We see ink on a page. The question is what makes the letters; is it the ink itself or the whiteness that surrounds the ink? Seeing only the ink is the masculine perspective: it's what first hits you, it's bold, it's pronounced, and it makes a lot of noise. In truth, however, it's the blank space around the ink that defines the words and letters. Like a sculpture, it's what you chisel away that gives it its sharp definition, otherwise it would just be a meaningless blotch of ink. It's what's not there that comprises the real story. This is the feminine perspective; it's subtle, deeper, more profound, the clearest illustration of the intangible vs. the tangible."

Granted, I tend to receive many if not most stories "yeshivically," if you will, after my stint at a rabbinical college ("you can take the boy out of yeshiva, but..."), yet this particular analogy is especially salient. In Michael Glover Smith's deft drama, three young couples repair to a house in the country for a recreational getaway weekend. One night, as the men convene for their literature club over scotch and cigars, the women venture to a bar in the nearby town to fashion their own ad hoc literary powwow. As the former group debates plot and character detail in Dashiell Hammett's The Glass Key, the latter group recites their favorite poems -- mostly by heart -- and plumb decidedly deeper aspects of their carefully selected subjects. The ladies' night out evolves into a therapy session for two of these finely and fully etched female characters, both of whom harbor pained secrets that consume them. Meanwhile, the men's smoky river of booze and bullshit subsumes them, rendering them almost momentarily anonymous, defined only by what seems to be, slaves to the deceptive appearance of normality and equilibrium. We learn through the women how misleading these illusions and self-delusions are.

This indicates a director concerned less with blotches of ink on the page (i.e. broad strokes of plot) than the sculpted, all-important tabula rasa that surrounds it (i.e. the emotional vicissitudes that surround his simple but effective setup). To return to the earlier established motif, it is Talmudic to invoke in text the words of great rabbis of Jewish scholarly history, and the provenance of those words cement the soundness of a given nugget of wisdom. In this case, I'll do so cinematically. In the name of the Rabbi Orson the Great, Rabbi Jaglom relates, "As for me, I act and give of myself as a man, but I register and receive with the soul of a woman. The only really good artists are feminine, you know. I can't admit even the existence of an artist whose dominant personality is masculine." (These are Orson's words as related in the book My Lunches With Orson.)

"In Asia," my old rabbi informs me, "there is a whole school of art based on this painting by focusing on the empty spaces rather than on the strokes themselves." Smith's most obvious and explicitly stated influence as a filmmaker is Eric Rohmer. The mark of a Rohmer acolyte is indeed present, though one is welcome to take a deeper exegetic dive that might yield less instantly logical parallels. He dedicates his Cool Apocalypse (2015) to Alain Resnais and Harold Ramis, a combination he agrees is curious. Smith's films are bracingly, conspicuously literate. His characters are predominately intellectual, which for me suggests Louis Malle and Jean Eustache, with maybe a chaser of Whit Stillman. Stylistically, his use of color and anamorphic widescreen in Mercury in Retrograde suggests the Vincente Minnelli of the fifties and sixties, especially the use of radical primaries in Some Came Running (1958) and The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse (1962).

I was also reminded of a scene in Arthur Hiller's Married to It (1993), a more commercially pitched movie that fared poorly with critics, in which three diverse couples in differing stages of their respective marriages become friends. While the men (Beau Bridges, Ron Silver, Robert Sean Leonard) go off bar-hopping at a dive and ogle the female specimens in the vicinity, the women (Stockard Channing, Cybill Shepherd, Mary Stuart Masterson) convene at Petrossian for champagne, memory-swapping, and comparing notes vis-a-vis la boudoir. It's a simple, familiar enough concept for a sequence in a film about couple mechanics, but Glover Smith expectedly probes its possibilities and implications in a far deeper way. Alan Alda's The Four Seasons (1981) covers similar thematic and narrative ground. (Incidentally, I'm of the mind that Hiller's picture was unfairly treated, and it remains a familiar rainy day favorite, or guilty pleasure if you will.)

As in Truffaut, these characters either recur or exist in the same universe. In Mercury in Retrograde, the character Richard (Kevin Wehby) explains that conspiracy theories are comforting "because they make it seem as if everything is connected." Within the so-called "MGS Universe," this is multifarious. On one level, the filmmaker is indeed covertly (and sometimes not so covertly) connecting his filmic worlds in a very literal sense. He also establishes human interrelationships that are burdened and sometimes even oppressed by what is left unsaid, and therein lies the next "comforting conspiracy," especially so because Glover Smith is hospitable to the audience in allowing access to the internecine clashes of heart and mind that addle and stymie his characters. We know them, and we come to know the individual nature of the weight they carry. All this, again, occupies the spaces "around the letters" -- and around the story as we know it. To watch them ping-pong off each other is quite the study.

The final vignette in his most recent Rendezvous in Chicago finds Julie (Nina Ganet) seducing us, the audience, and our proxy, the camera, after catching boyfriend Wyatt (Shane Simmons) en flagrante delicto with another woman. The character Julie first emerges years earlier in Cool Apocalypse, while Wyatt emerges in Mercury in Retrograde. Their re-emergence here is a fitting apotheosis. At the end of an unofficial ad hoc "trilogy" involving an implicit network of satellite characters circling each other in carefully choreographed pas de deuxs, what could be more perfect than seeing these mix-and-matches burn out in favor of a literal pas de deux with the camera? By rendering us the first-person object of affection, he completes the circle in a most deliciously cockeyed way.

On a personal note, in showing my own longtime cinematographer the first vignette in Rendezvous in Chicago, which involves a comically suspenseful game of "strip literary trivia," he observed, "It's so hard fashioning an interesting 20-minute episode almost entirely around a shot-reverse-shot dialogue between two characters, but this sings. It is quite remarkable." I knew he would appreciate it, for its erudition, its sly wit, and above all, seeing a challenge of staging addressed with a bravado all too rare in the annals of current American independent cinema. Beyond that, it's plain old fun, a veritable hoot, and it is clear that the actors and their director approach it much the same way as those unsuspecting audiences who witness the delivery.

Michael Glover Smith has an acute understanding of the rhythms and codes infused into even the most simple and innocent encounters -- that is, he compels us to consider the "ink" on his "page" and the void that surrounds his fastidiously inscribed letters. He wraps these rhythms and codes in a cocoon of potential explosiveness, and gauges them for varying degrees of detonation. All of this is achieved with a formidable degree of cinema literacy, the tenor of which is vital, embracing, perspicacious, and passionate. Best of all, in his vigor, Glover Smith calibrates all this to be contagious.

And he is in thrall to his beloved home city Chicago in a way that would make pioneering silent-era "city symphonist" filmmaker Walter Ruttmann (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City) dance in his grave.

Overwhelm the Sky and the Upcoming "Small Gauge Trilogy"

Daniel Kremer's epic Overwhelm the Sky screened at the San Francisco Independent Film Festival (SF IndieFest) on February 10, 2019. The film and its director were also the subject of a recent interview in Filmmaker Magazine. It has two premiere engagements at European festivals in the spring and summer (they cannot be named specifically until the news is official). San Francisco's Roxie Theater will also host an exclusive roadshow-edition screening event, featuring souvenir printed programs, assigned seating, and an Overture/Intermission/Entr'acte format, to emulate the epic-length "event pictures" of the 1960's. The film's official trailer can be viewed here. Acclaimed filmmaker Michael Glover Smith (Mercury in Metrograde, Cool Apocalypse, Rendezvous in Chicago) said of Overwhelm the Sky: "A masterpiece. The filmmaking is so confident that it's astonishing. The paranoid atmosphere, the perfectly calibrated camera moves, the always surprising but ineffably right compositions, and the precision of the cutting, reminded me of Paul Thomas Anderson."

Kremer is also at work on the Small Gauge Trilogy, a trio of feature films with unique narratives focused on the robust life that exists inside and around small-gauge film formats (i.e. 8mm, super-8, 9.5mm, 16mm, 17.5mm). The trilogy currently consists of Even Just (coming summer 2019) and Surface Pressures (coming early 2020), with the third entry in the development stages.

Even Just (the first in the trilogy), starring Joel Roth (star of the feature comedy/drama Roxie), follows a two-bit "ambulance chasing" accident lawyer's obsession with the many 8mm film elements he has collected since childhood; because he's an incurable dreamer, his obsession comes at a detriment to his livelihood. Even Just's first teaser can be viewed here. Surface Pressures (the second in the trilogy) is a loose adaptation of an Alberto Moravia novella that incorporates 8mm and 16mm found footage, with music, narration, re-recorded dialogue, and meticulously constructed soundscapes.

Hester Street and the Cinema of the Pilpul

The new management regime at Fandor, in their wisdom (read: stupidity), zapped their online film magazine and blog Keyframe, and with that, their entire archive of articles. No record of any of the authors' work -- all gone. So I've republished here.

Last year, while producing and editing “kosher media” for a video production company in Brooklyn, I became friendly with an elder Yiddish theater actor who often worked with us on assorted commercials and music videos — a stout, pint-sized man with a stubbly but no less angelic “Yiddishe punim” (Jewish face) who could effortlessly affect a stereotypical East-Side-by-way-of-Flatbush “alter kocker” patois that put anyone in the vicinity in stitches. The right Jewish word to describe him is "heimishe" (exceedingly friendly, unassuming, welcoming, unpretentious). One night, he ventured into my editing room from the adjacent studio to visit me while I was hard at work, as the crew set up for his next shot. After he recounted starring in a Yiddish-language production of Waiting for Godot, we proceeded to talk on the subject of “mama loshen” (mother tongue), and about the specific richness of Yiddish as it related to Hebrew.

So, now back to the Yiddish theater actor, who then saw fit to extol the virtues of the Yiddish language, although I think he knew he was preaching to the choir. My own heart pines and prances at the utterance of Yiddish, a language to which I listen fluently but speak haltingly (though my everyday speech is sprinkled with Yiddish-isms, some overt and foreign, and others commonly adopted into the English lexicon). He then said something that I deemed rather profound: “Yiddish is a thing of beauty because it’s the language of the pilpul…it’s the language of compromise.” According to him, modern Hebrew originally bred and continues to breed a fierce brand of Jewish nationalism and exceptionalism that worries him (I personally do not subscribe in any way to this view, but I can, in my own way, understand his basic logic – and this could indeed easily be the subject of another article, but I will of course stick to the topic at hand).

Since November 2014, I’ve been working with Oxford University Press on the first biography on director Joan Micklin Silver, known for Crossing Delancey (1988), Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979), Between the Lines (1977), and her breakthrough feature Hester Street (1975), starring Carol Kane in one of the earliest independent film performances to be nominated for the Academy Award. Most of Silver’s films find comic discomfort in juxtaposing the “old world” with the modern world. Her skill as a director lies in orchestrating pathos and often unexpected humor that occur when these worlds collide. That many of her films are Jewish-themed is certainly apropos to this, her most burgeoning theme, but even the ones that do not broker in outwardly Jewish subjects are steeped in this narrative conflict – of characters with a death-grip on their memories of a halcyon past, or a way of life, who find themselves at odds with moving forward in the status quo. Their death-grip makes them pragmatically and emotionally vulnerable.

That much of the film Hester Street is performed in the Yiddish language is auspicious, but it engenders another kind of perfection, especially when one considers what the Yiddish theater actor expressed to me, about what the beauty of Yiddish really means to him. The film is, in many ways, about compromise amid complexity, staged in a language with this heritage of compromise and complexity, and one that extends beyond just cultural or religious baggage.

Near the end of Hester Street, Carol Kane’s Gitl has stayed true to herself, but has learned, and quite fast, these new American ways. The moment when she admonishes the character of Mrs. Kavarsky for referring to her son “Yossele” rather than the now-accepted “Joey” defines the cinema of the pilpul. There is a gentle awareness that this moment of Americanization is something for which a delicate balance must be struck. She must now tend to the tall order of conforming the present reality with her earlier expectation – one now shrivelled into a simple but no less impassioned dream – of being able to keep the identity-defining traditions of her rooted past alive.

Last year, while producing and editing “kosher media” for a video production company in Brooklyn, I became friendly with an elder Yiddish theater actor who often worked with us on assorted commercials and music videos — a stout, pint-sized man with a stubbly but no less angelic “Yiddishe punim” (Jewish face) who could effortlessly affect a stereotypical East-Side-by-way-of-Flatbush “alter kocker” patois that put anyone in the vicinity in stitches. The right Jewish word to describe him is "heimishe" (exceedingly friendly, unassuming, welcoming, unpretentious). One night, he ventured into my editing room from the adjacent studio to visit me while I was hard at work, as the crew set up for his next shot. After he recounted starring in a Yiddish-language production of Waiting for Godot, we proceeded to talk on the subject of “mama loshen” (mother tongue), and about the specific richness of Yiddish as it related to Hebrew.

A quick history lesson: The early Zionist movement in the

late nineteenth and early twentieth century hotly debated what the official

language would be, should the Jews eventually achieve statehood. Religious Jews contested the Hebrew

option because of its nature and background as “loshon kodesh” (holy tongue), a

language only to be spoken in religious context rather than in everyday

speech. However, to progressive,

secular Jews, the Yiddish language, a flavorful combination of Hebrew, German,

Russian, and Slavic languages, signified the chains of a difficult past in “old

world” Jewish Europe, with its perceived antiquated values, its stifling

strictures, and its persecution.

In short, to secular progressives, it reaked of what they deemed

backwards provincialism.

Ultimately, newspaper editor and lexicographer Eliezer

Ben-Yehuda revived “loshon kodesh” by becoming the author of the first “modern

Hebrew” dictionary. Today, the

Hebrew/Yiddish schism is no longer the issue it once was; Hebrew as a

conversational language is accepted as a fact of life in Israel, even among the

observant (though Yiddish still thrives in this significant segment of the

demographic). Although most of

today’s American Chassidim are Yiddish monoglots, the language of Yiddish is

rapidly dying off outside these Chassidic enclaves. And it continues to die every day the Jewish elderly pass

into eternity.

So, now back to the Yiddish theater actor, who then saw fit to extol the virtues of the Yiddish language, although I think he knew he was preaching to the choir. My own heart pines and prances at the utterance of Yiddish, a language to which I listen fluently but speak haltingly (though my everyday speech is sprinkled with Yiddish-isms, some overt and foreign, and others commonly adopted into the English lexicon). He then said something that I deemed rather profound: “Yiddish is a thing of beauty because it’s the language of the pilpul…it’s the language of compromise.” According to him, modern Hebrew originally bred and continues to breed a fierce brand of Jewish nationalism and exceptionalism that worries him (I personally do not subscribe in any way to this view, but I can, in my own way, understand his basic logic – and this could indeed easily be the subject of another article, but I will of course stick to the topic at hand).

Let us rewind for a moment. What is this strange word “pilpul”? No, it’s not like kugel, and is not in

any way edible, although it does originate from the Hebrew word for

“pepper.” However, it is one of

the very few Talmudic vocabulary words to have been appropriated into the

standard English dictionary, though the word still remains obscure relative to

other Jewish-rooted crossover classics like “schlep,” “schtick” and

“kvetch”. Defined by

Merrian-Webster, “pilpul” is “hairsplitting critical analysis.” You could also call it “heavy-duty

exegesis.”

As the old adage goes, “Two Jews: three opinions.” In the course of rabbinic dialectic and

Jewish learning, one is to accept the inherent complexity as it exists in everything

under the sun. And in order for

our all-too-human hearts and minds to reconcile that which seems

irreconcilable, a careful manner of compromise must be applied and weighed in

accordance with all the conceivable factors. Thus, Yiddish as a conflagration

of many languages, is a language of compromise, just as pilpul is based on

putting compromise into action in an effort to make it meaningful.

So, all this extraneous info just to introduce a film? I know, this stuff’s getting dense, but

bear with me. I guarantee that it

all has a point, and I think a valuable one important to cinema as a whole.

Since November 2014, I’ve been working with Oxford University Press on the first biography on director Joan Micklin Silver, known for Crossing Delancey (1988), Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979), Between the Lines (1977), and her breakthrough feature Hester Street (1975), starring Carol Kane in one of the earliest independent film performances to be nominated for the Academy Award. Most of Silver’s films find comic discomfort in juxtaposing the “old world” with the modern world. Her skill as a director lies in orchestrating pathos and often unexpected humor that occur when these worlds collide. That many of her films are Jewish-themed is certainly apropos to this, her most burgeoning theme, but even the ones that do not broker in outwardly Jewish subjects are steeped in this narrative conflict – of characters with a death-grip on their memories of a halcyon past, or a way of life, who find themselves at odds with moving forward in the status quo. Their death-grip makes them pragmatically and emotionally vulnerable.

The prospect of this particular book project excited me at

my deepest core. As an observant

Jew myself, one who once attended a Chabad-Lubavitch yeshiva with the intention

of entering the rabbinate, I felt especially equipped and ready to tackle the

Jewish subject matter in her films in a way that no other author would or

could.

Usually, in examining films about observant Jews, I find

myself yelling at the screen as a result of a filmmaker’s outright negligence, dumbfounding

errors, and exotification. Sidney

Lumet’s A Stranger Among Us (1992) is a major bête noire for me. Counter to pictures like Lumet’s

disposable, embarrassing depiction of New York Jewish subculture, Hester Street

and Crossing Delancey don’t soft-peddle their Yiddishkeit. On the contrary, they get so much

right, and render the subject matter with palpable respect and great love.

Beyond my great admiration for Joan’s corpus, the book is an

opportunity for me to braid the threads of my unusual double life. And as it so

happens, my dream film project is an epic adaptation of Abraham Cahan’s novel

The Rise of David Levinsky, which you might say is a Jewish Horatio Alger tale,

by way of Dostoevsky.

That much of the film Hester Street is performed in the Yiddish language is auspicious, but it engenders another kind of perfection, especially when one considers what the Yiddish theater actor expressed to me, about what the beauty of Yiddish really means to him. The film is, in many ways, about compromise amid complexity, staged in a language with this heritage of compromise and complexity, and one that extends beyond just cultural or religious baggage.

Now consider this: Silver made her debut feature in direct

defiance of the standard system of motion picture production -- a system that

saw her simply as a wannabe filmmaker handicapped by shear virtue of her

gender. As I state in the opening

line of the book, “A female first-time director wanted to make a black-and-white

film about immigrant Jews coming to America in the early twentieth

century. This single statement,

though seemingly harmless, was at that time fraught with at least five

potential hazards.”

In choosing to adapt Yiddish Daily Forward founder Abraham

Cahan’s novella Yekl, she automatically committed a form of commercial

suicide. The very first Hollywood

studios, which had been famously founded and owned by Jews eager to chuck this

aspect of their identity, were rooted in a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy

regarding questions of Jewishness in their product.

These studio heads, who “went from Poland to polo in less

than one generation,” lived in a world where it paid to be covert – and where

it was kosher, for instance, to bribe the lone non-Jewish studio head, Darryl

Zanuck of Fox, to permanently shelve his drama Gentleman’s Agreement (1947), an

exposé of anti-Semitism. The

bribing party, Louis B. Mayer, Jack Warner, Carl Laemmle and Harry Cohn, set

the stage for a persisting Jewish denial in Hollywood, which in turn cultivated

the belief that outwardly Jewish content ran counter to commercialism. The studio founders’ successors

inherited this sentiment, so one can then understand how the Cahan property was

not accepted as a pedigree for success.

Hester Street and its source Yekl, both set circa 1900, tell

the story of an Americanized Jew who has “shpilkes” (anxiousness) to

assimilate. He has shed the appellation “Yankel” for the more socially

acceptable American name “Jake”.

He also manages to dress like a dandy on his meager earnings as a sewing

machine operator in the garment district.

When he imports his wife Gitl and his five-year-old son Yossele, no

sooner are they off the boat before he goes on a campaign to Americanize them. Gitl, however, refuses to hear of it,

as she stays steadfast to the old ways.

She keeps her sheitl (wig), sprinkles salt in her little boy’s pockets

for luck, and tries to proposition a visiting peddler about obtaining a liebe

trop’n (a love potion) so that her husband will love her anew. "I won’t

look like a goy, even for Yankel,” she exclaims to Mrs. Kavarsky, their

busy-body landlady. All the

while, however, she slowly finds herself going sweet on Jake’s Talmud scholar

roommate Mr. Bernstein.

Near the end of Hester Street, Carol Kane’s Gitl has stayed true to herself, but has learned, and quite fast, these new American ways. The moment when she admonishes the character of Mrs. Kavarsky for referring to her son “Yossele” rather than the now-accepted “Joey” defines the cinema of the pilpul. There is a gentle awareness that this moment of Americanization is something for which a delicate balance must be struck. She must now tend to the tall order of conforming the present reality with her earlier expectation – one now shrivelled into a simple but no less impassioned dream – of being able to keep the identity-defining traditions of her rooted past alive.

Hester Street is cinema that is both of and about compromise

– the pilpul, as it can exist on celluloid at its most lively.

When one also considers the lengths to which Silver had to

go, to finance, shoot and then distribute Hester Street, it only enriches the

point. With only $500,000 raised,

Silver had to evoke the early twentieth century on the precious, dangerously

limited funds allotted to undertake such an endeavor. When no distributor evinced an interest in picking up the

film, and in the face of the suggestion that it could “play the synagogue

circuit,” she and her husband Raphael “Ray” Silver self-distributed (with the

help and advice of John Cassavetes and Jeff Lipsky). It was a pure go-for-broke endeavor – what indendent cinema

is really about, or at least should be about. At least it is what I, and my filmmaking friends, think it

is about.

Independent cinema of this variety is so often about finding

the art and beauty in compromise, while at the same time being

uncompromising. It is an

appropriation of the pilpul. Am I

saying making a film is Talmudic?

Yes, in a way, I am. As

Orson Welles once said, “The enemy of art is the absence of limitations.” All of this makes Hester Street an

absolute must-see picture in my book, for Jews, Gentiles, and especially

filmmakers (which I deem as much a religious group as any of them).

At this point in my own personal spiritual journey, I’m

comfortable with attending my local shul (synogogue) regularly here in San

Francisco’s Noe Valley, and then, as a filmmaker, attempting to make

emotionally honest pictures that wouldn’t really qualify as kosher in any

traditional sense of the term. But the act of storytelling is ingrained in

Jewish culture, and stories told leave an indelible mark that Judaism

acknowledges. I search for my own beautiful compromise.

Fandor now premieres Hester Street, one of my favorite

films, brought to you by the great Joan Micklin Silver, a director sorely in

need of further consideration and discussion.

Next Book Project Announced: Nothing Too Personal: The Life and Films of Henry Jaglom

PRESS RELEASE [November 19, 2017]: While Daniel Kremer edits both his seventh feature-length film, Overwhelm the Sky (due in summer 2018), and his second book Joan Micklin Silver: From Hester Street to Hollywood (due in early 2019 from Oxford University Press), he has started researching Nothing Too Personal: The Life and Films of Henry Jaglom, the first book on the American independent cinema icon behind such art-house hits as Eating (1990), Can She Bake a Cherry Pie? (1983), Tracks (1976), Always But Not Forever (1985), Someone to Love (1987), and many others. Kremer and Jaglom (pictured above) just completed their first round of taping sessions in Los Angeles, and accumulated over 20 hours of recorded material. The two have known each other close to fourteen years, and both are very excited about the project.

The book will feature never-before-reported stories involving legends like Judy Garland, Ingrid Bergman, Marilyn Monroe, Lee Strasberg, Groucho Marx, Jerry Lewis, Frank Sinatra, Gene Kelly, James Mason, Abbie Hoffman, Huey Newton, and countless others.

Kremer's film Ezer Kenegdo (co-directed with Deniz Demirer) went into release earlier in November after its world premiere at the prestigious Joseph Conrad Festival in Krakow, Poland. The River's Edge International Film Festival hosted its U.S. premiere. It is now touring international film festivals.

Shooting will soon re-commence on Kremer's biographical documentary Sidney J. Furie: Fire Up the Carousel! (due in 2019) after a year-long hiatus; Furie is now gearing up for the production of his next (and final) film, Hannah Cohen, a Holocaust story set throughout Israel. Kremer will be there to capture the making of Furie's swan song (perhaps the most important film of a 60+-year career), which will hopefully enhance his in-depth cinematic portrait of one of his favorite directors.

With film historian Howard S. Berger, Kremer recently provided a full-length commentary track for the Kino Lorber Studio Classics DVD/Blu-Ray release of Furie's The Taking of Beverly Hills (1991). More details here. It is a rather curious but fun-fun-fun track that covers a misbegotten entry from Furie's later-career tenure as an action director.

Kremer will also be starting production on his eighth feature film Even Just in December. The film (possibly a musical, wink wink) will star Joseph Badra (making his film debut), Penny Werner, and Carol Carbone.

Overwhelm the Sky now has a teaser. Raise Your Kids on Seltzer (2015), which Kremer and ConFluence-Film released in 2015, now has a post-release trailer.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)