Before I begin the article proper, I would like to thank fellow blogger Chris Cagle at the Category D blog for sending me the screen-captures I requested for this entry, and friend Sunrise Tippeconnie for inspiring the section that discusses the sub-conscious art of pan-and-scan.

I remember a film professor saying in my first year of college, “If ever you want to be able to watch a film like a normal viewer again, leave film-school here, now, and leave it real quick…because I’ll tell you plain that you won’t even be able to watch a Pauly Shore movie again without looking at how it’s all lit or deducing what film-stock was used, and all manner of stuff no average Joe would even think or care to consider.” Granted, I was already a hardened cinephile before going off to study film at school, but I never had the urge to deliberate in any depth about filmmaking technicality or practical technique. Nevertheless, at the time, I took the warning with a grain of salt.

I thought of my old professor’s warning again recently when stopping off at a local video-store on my way back home one night and finding myself scouring the shelves compulsively looking at aspect ratios listed on the back of the video-covers there, hypothesizing in the split-second between picking one up and finding the place on the back-cover where aspect ratio was (hopefully) listed in its exactitude. This isn’t the first time I had done this. In all honestly, in the last three months, this habit has become a compulsion…an obsession within my obsession. But there is a reason behind this obsession, and I feel an important one: What compels a given filmmaker to shoot a given film in a given aspect ratio (beyond any obvious reasons, like equating the word “epic” with wide Scope aspect ratios), and can you properly motivate an aspect ratio choice in a strictly aesthetic sense? Can it be a really qualify as a full-fledged tool in the filmmaker’s arsenal? After all, with a simple change of aspect ratio, your whole perspective on the material can change. Thus, when I say that I “hypothesized” before picking up these covers in the video store, it was me deducing the frame-size for each individual title based on possible motivations.

In the midst of my prepping a feature-length project entitled Permanent Arrangements which I am writing and directing next year, the aspect ratio question became one that quickly plagued me. “What should I use…and, most importantly, why should I use it?” I began a process of finding interesting cases of aspect ratio uses, such examples being Robert Altman’s 2.35:1 lensing in Images (1972) and 3 Women (1977). Permanent Arrangements is ostensibly a film on an intimate scale, but ultimately and despite an initial bit of “intimate = 1.85, 1.66 or 1.33” equation-making, I was facing the idea of my personally using the 2.35:1 aspect ratio for the first time in my own work. In my past work, this prospect never once entered my mind, so I attempted to analyze possible motivations involving case studies of films with puzzling, noteworthy aspect ratio choices.

In the midst of my prepping a feature-length project entitled Permanent Arrangements which I am writing and directing next year, the aspect ratio question became one that quickly plagued me. “What should I use…and, most importantly, why should I use it?” I began a process of finding interesting cases of aspect ratio uses, such examples being Robert Altman’s 2.35:1 lensing in Images (1972) and 3 Women (1977). Permanent Arrangements is ostensibly a film on an intimate scale, but ultimately and despite an initial bit of “intimate = 1.85, 1.66 or 1.33” equation-making, I was facing the idea of my personally using the 2.35:1 aspect ratio for the first time in my own work. In my past work, this prospect never once entered my mind, so I attempted to analyze possible motivations involving case studies of films with puzzling, noteworthy aspect ratio choices.Faces vs. Spaces

Let us start simple. What is the function of an aspect ratio? Easy! To establish the wideness of the frame. Okay. But also, in taking it to the next level, to define the overall sense of screen space, and to frame the intricacies of a film’s mise-en-scene in degrees of wideness. So, back to the question that plagues me and this article: Can you motivate it, in the way that you can properly motivate lighting and performance? For filmmakers, there would seem to be two implied equations. Epic = panorama and spaces, thus 2.00, 2.20, 2.35, et al. Small and intimate = close-ups, thus 1.85, 1.78, 1.66, 1.33 (full-frame). Often, these two equations govern filmmaker choice. What happens in the anomalous cases when the equations are reversed, hence when “epic = close-up” and “intimate = space and Scope”. The frequency with which Robert Altman has used 2.35 throughout his career is striking, as he has used it in the two titles mentioned above and other cases when such a choice would not be motivated in any traditional sense. It is understandable in films like Nashville and Short Cuts, in which he uses a meaningful and motivated 2.35 in an effort to define a “social space”. However, Images and 3 Women are two films that are neither about using the wide-frame as a stage for the social space, nor to function in evoking tableau, which Altman proved to be fond of throughout his career.

Steven Soderbergh's recent feature, the "intimate" The Girlfriend Experience , was shot with an aspect ratio of 2.40:1, and uses voided space and shallow depth-of-field in close-ups.

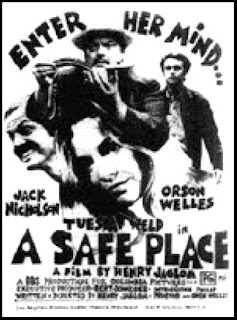

Steven Soderbergh's recent feature, the "intimate" The Girlfriend Experience , was shot with an aspect ratio of 2.40:1, and uses voided space and shallow depth-of-field in close-ups.In the two Altman films, the use of screen-space is very deliberate and constantly motivated. Seeing these films again and reassessing them in these new terms was the original impetus behind my pondering (and ultimately deciding in favor of) shooting my upcoming film on 2.35. For instance, in the case of Images, a so-called “puzzle film” and a character piece ostensibly about an isolated (and possibly schizophrenic) woman’s complex string of hallucinations and fantasies, the wide 2.35 space addresses the character’s uncertainty about what lurks often stealthily within her environment and the spaces she inhabits—the insidious visions of a past that villainously haunts her can occur a number of places in the frame, much more so than if Altman has chosen a less “ambitious” aspect ratio. The character's visions can present themselves in more places throughout the frame, with more spatial options. So, when all is said and done, Altman hereby uses the wide frame to open up the film’s spaces to depict the uncertain psychological landscape of his lead character, all with aspect ratio! In the case of my own project, a similar narrative situation presents itself, i.e. an uncertainty about the spaces that surround the two primary characters, so I would intend to use the widened frame to evoke that lack of an overall feeling of safety and control in both the audience and the characters. This is not just a cerebral exercise, as some may feel it is. Choice of an aspect ratio, in my mind, can convey just as much as lighting, mood, performance and the other elements of the medium.

I feel there is a common misconception about the role and presentation of the close-up in the anamorphic frame. In the words of another teacher, a skeptic about anamorphic aspect ratios I might add, “Ahhh, close-ups in anamorphic! You’ve got the face on one side, and you gotta put a lamp or something on the other side.” I always thought was rather facile. Look at the case of George Cukor’s A Star is Born (1954). The CinemaScope camera navigates the spaces of the story so fascinatingly and effortlessly (e.g. the “Man That Got Away” sequence), yet we feel so very in touch emotionally with the characters on display in moments of close-up, perhaps even as a result of seeing how the characters fall within these spatial navigations. A Star is Born is an extraordinary film when we consider the idea of space—its faces and spaces.

Early Spielberg demonstrates mastery of what I’ll call “the intimate Scope," often with the use of triangular compositions (see above), where our attention is drawn to three components onscreen. In The Sugarland Express (1974), for a large part of the film, we are looking at and listening to three characters traveling in a car. Likewise is the case with Two-Lane Blacktop (1971). The respective cinematographers’ uses of the 2.35 frame contribute to the films’ compelling visual qualities. Space is usually occupied and is rarely ever idle. Spielberg and Hellman motivate their spatial framing choices by using the wider aspect ratio. The domestic scenes in both Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind also demonstrate Spielberg’s control of the intimate Scope. Spielberg is very affectively able to use split diopter shots (i.e. a shot in which two distinct fields of focus are both made sharp and in-focus through the use of the bifocal lens) because of the wide frame. Brian De Palma was also fond of using split-diopter shots in films like Dressed to Kill and Blow-Out, as was Wim Wenders in Paris, Texas. The opportunity for novel use of the split-diopter shot is greater in a Scope aspect ratio. See below.

Early Spielberg demonstrates mastery of what I’ll call “the intimate Scope," often with the use of triangular compositions (see above), where our attention is drawn to three components onscreen. In The Sugarland Express (1974), for a large part of the film, we are looking at and listening to three characters traveling in a car. Likewise is the case with Two-Lane Blacktop (1971). The respective cinematographers’ uses of the 2.35 frame contribute to the films’ compelling visual qualities. Space is usually occupied and is rarely ever idle. Spielberg and Hellman motivate their spatial framing choices by using the wider aspect ratio. The domestic scenes in both Jaws and Close Encounters of the Third Kind also demonstrate Spielberg’s control of the intimate Scope. Spielberg is very affectively able to use split diopter shots (i.e. a shot in which two distinct fields of focus are both made sharp and in-focus through the use of the bifocal lens) because of the wide frame. Brian De Palma was also fond of using split-diopter shots in films like Dressed to Kill and Blow-Out, as was Wim Wenders in Paris, Texas. The opportunity for novel use of the split-diopter shot is greater in a Scope aspect ratio. See below.

A Dying Compromise

It is most fair to assume that the days of pan-and-scanning are well over and that they died along with the popular use of the VHS videocassette. Directors like Kubrick and Sidney Lumet were never keen on shooting anamorphic. Kubrick shot his films in matted 1.85 (cropped 1.33) following A Clockwork Orange and Lumet never shot a film in 2.35 in his entire career (perhaps due to his background in directing television in the 1950's). Rightfully, directors were frightened of a compromised frame when their films were prepared for television showings. More, of course, would be lost in the Scope frame rather than in other aspect ratios. For fun, I used the Zoom function on my DVD player to have a look at what two of my films would look like pan-and-scanned, and I was horrified, counting my lucky stars that I am coming of age as a filmmaker when the rule of preserving aspect ratios for the home-theater market has been upheld. I still, however, often use the Zoom function whenever I’m curious to how my experience of viewing a cropped version of a film greatly differs from the “uncompromised” film. These days, I do this whenever a new DVD goes in the tray.

I have an unbelievably vast and mountainous collection of VHS tapes and, within this collection, I can point to many examples of pan-and-scan in all its

Okay, so the pan-and-scanner fell asleep at the wheel. Now what have we got? Above me, you will see two screen captures from Irma La Douce (1963) and below them various permutations of cropping and p&s-ing. This is an effort to prove pan-and-scan as a sort of revisionist art (think of the subconscious art of graffiti removal, a la Matt McCormick's amusing short film The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal). Using the logic of sequencing and the meaning we can get from sequence, let's see what happens for a few sequences of these two shoots put together when visual information is lost.

Okay, so the pan-and-scanner fell asleep at the wheel. Now what have we got? Above me, you will see two screen captures from Irma La Douce (1963) and below them various permutations of cropping and p&s-ing. This is an effort to prove pan-and-scan as a sort of revisionist art (think of the subconscious art of graffiti removal, a la Matt McCormick's amusing short film The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal). Using the logic of sequencing and the meaning we can get from sequence, let's see what happens for a few sequences of these two shoots put together when visual information is lost.1A: We see the selzer-shooter in the first shot so we know where the seltzer is coming from, and we see the person getting hit directly with it in the next shot, our main character (Jack Lemmon) has been cropped out.

2A: "Wuh??? Hey, where's dat seltzer comin' from???"

2B: "What's that thing over Lemmon's head?"

3C: "What, is that guy in the hat conjuring and projecting the seltzer over Lemmon's head using telekinesis or something?"

1C: Perhaps the best of the combinations, despite the visual information being lost, but hark, where's that line coming from spoken after the seltzer flow stops?

I have a vague memory of a shot in my Magnetic Video pan-and-scan with Lemmon on the left side of the screen and Lou Jacobi (the selzer-shooting, tale-spinning bartender) on the right side of the screen, and the image cropped to show neither Lemmon nor Jacobi but the seltzer-stream in center-screen. In a VHS I own of Otto Preminger's Rosebud (1975), Peter O'Toole on screen-right and Claude Dauphin on screen-left have both been cropped out to reveal (get this) the empty middle of the frame! The pan-and-scanner either liked the color of the wall or was catching Z's for what was probably his umpteenth cropping job of the day. Not only this, but as I mentioned, different video companies had very distinctive pan-and-scanner styles. MGM/UA physically panned the wide-frame the most (a pan-and-scan of Victor/Victoria I recently purchased for $1 is a fascinating case-in-point), Paramount tried to pack as much information as they could into the frame (e.g. an early Catch-22 pan-and-scan). And Columbia in the 90's...don't watch those VHSs if you get motion-sickness easily.

I also researched extensively rare and seldom-used aspect ratios (e.g. the use of the 2.76 MGM Camera 65 and Cinerama processes in Ben-Hur and The Greatest Story Ever Told, and the use of 2.55 in Disney’s animated Sleeping Beauty). And last but not least, I researched fascinating cases of early video pan-and-scanning of super-wide aspect ratios. Honestly, my film study the last few months has been almost completely about motivating the aspect ratio. Often, I feel, young filmmakers (read: peers) shoot in 2.35 because it demonstrates certain ambition and a sense of professionalism and awareness, but never is a motivation considered. I hope I am broaching the possibility of shooting a film in 2.35 with being fully capable of explaining the choice.

I also researched extensively rare and seldom-used aspect ratios (e.g. the use of the 2.76 MGM Camera 65 and Cinerama processes in Ben-Hur and The Greatest Story Ever Told, and the use of 2.55 in Disney’s animated Sleeping Beauty). And last but not least, I researched fascinating cases of early video pan-and-scanning of super-wide aspect ratios. Honestly, my film study the last few months has been almost completely about motivating the aspect ratio. Often, I feel, young filmmakers (read: peers) shoot in 2.35 because it demonstrates certain ambition and a sense of professionalism and awareness, but never is a motivation considered. I hope I am broaching the possibility of shooting a film in 2.35 with being fully capable of explaining the choice.To access a fairly comprehensive list of American films shot anamorphically, click here. Below is Turner Classic Movies' little promo about letterboxing, no doubt created to field skeptic's complaints in the 90's when the movie network started.

POST SCRIPTUM: I recently considered the fact that John Landis' The Blues Brothers was shot in standard 1.85:1 aspect ratio. I realized that by changing the film's aspect ratio to 2.35 or 2.20, the film assumes a different role and a different way of functioning entirely. That particular film becomes more of a spectacle than it already is simply by enhancing the wideness of the frame, and becomes a different kind of genre piece entirely (despite the fact that the film meshes a good many genres). Consider this concept. I would like to hear your thoughts on this particular matter.