In the spirit of the article written last year about another unfairly forgotten and marginalized director who had been denied recognition, as an auteur with a rich body of work, I continue the tradition this year with British director Anthony Harvey. I write this article concurrent with drafting a book on my last subject, Sidney J. Furie. I am not “cheating on” Furie in the literary sense, as it were. (1) I feel the need to keep the blog alive while I complete the demanding book project, and (2) I need to give my mind an analytical exercise outside of the realm of Furie-ous films to give my analysis of those works more freshness, variation, distance and perspective. The Harvey analysis might inadvertently shed light on my Furie analysis.

Coming Soon: An article about the excavation and resurrection of the 35mm negatives of Sidney J. Furie's missing-in-action 1959 independent film A Cool Sound from Hell, thanks to the British Film Institute!

It's Oscar night,

1969. An ever-radiant Ingrid Bergman emerges to announce the

winner of undoubtedly the most anticipated award of the evening: the Best

Actress prize. The critics, the press

and the trades have been publicizing a neck-and-neck race between the seasoned

veteran Katharine Hepburn, who has won the coveted award twice previously, and

newcomer Barbra Streisand for her starmaking film debut as Fanny Brice in Funny Girl. Variety’s droll headline roars, “Funny Girl vs.

The Lioness.” As Bergman opens the

envelope, she is clearly flabbergasted. “The winn…,” she

starts to announce as her voice trails off. A bewildered double-take, followed by a

shocked demur, accented with a movement of the hand to cover her mouth in

amazement. “It’s a tie!” For the first

time in Oscar history, two performers are presented with the same award.

Hepburn, whose Eleanor of Aquitaine in The

Lion in Winter won nearly unanimous accolades, is not present to

accept the award herself. Accepting the

award on her behalf is her director, Anthony Harvey.

Arriving at the

podium flanking a radiatingly happy Streisand, he holds the statuette in his

hands and declares in a distinctly mellow-tenored “public school class” British

accent, “When I asked Ms. Hepburn what she thought when she had broken the

records for nominations, she said, ‘I suppose if you live as long as I have, anything

can happen.’” The audience murmurs a few courtesy chuckles. He

continues, “And I’m absolutely thrilled that it has happened. Thank you.” He steps aside as Streisand takes the podium

for her speech, gazing wide-eyed at her statuette and greeting it with a

now-classic Streisand salutation.

“Hello, gorgeous!” The audience

explodes in laughter. They’re in love

with her. Already, even at the height of

his fame, Anthony Harvey had been forgotten with undue haste, his awkward and

rare would-be cameo effectively upstaged. Thus marked a rare public appearance of Harvey, who himself was

nominated that same year for directing The

Lion in Winter, losing to veteran Carol Reed for Oliver!, that year’s most successful contender. The die, it would seem, had been cast.

Anthony Harvey

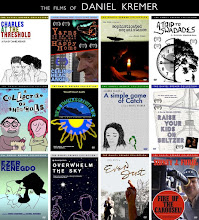

launched his career as a film editor on many British productions of the 1960’s. Both Stanley Kubrick and Bryan Forbes

regularly employed him, namely on Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove (1964), the criminally underrated The L-Shaped Room (1962) and The Whisperers (1966), and both Martin

Ritt’s The Spy Who Came In from the Cold

(1966) and Guy Green’s The Angry Silence

(1959) bear his name as film editor. He

made his directorial debut with the 55-minute Dutchman in 1967, which earned its lead actress Shirley Knight an

acting award at the Cannes Film Festival.

The Lion in Winter, undoubtedly the most prominent, most critically beloved and most commercially successful film Harvey directed, did not provide

my own personal introduction to his work.

At the age of fourteen, I came into possession of the Rank Organisation-bankrolled British Western Eagle’s Wing (1979)

on a pan-and-scan VHS. Little did I know

at the time that the film had been beautifully lensed by Billy Williams in

anamorphic widescreen and that I was missing almost half the full frame on this

video copy. The epic

splendor of the images, cited by even the film’s most virulent detractors, was

more than a little lost on me, but I still nonetheless took note of its strange

pacing — a pace that was particularly at odds with a story that pitted four

separate components of a chase narrative against one other. I might have been looking at a Western

produced by men fond of regular daytime tea breaks, but I started to recognize

a method to the ostensible “madness” inherent in the conflicting rhythmic and

narrative elements. In the subsequent

years, I came to see most of the other works in Harvey’s directorial

canon. Recently, I had the occasion of

seeing both Richard’s Things and the

only recently released widescreen version of Eagle’s Wing. Both incited

the writing of this, the first formal written work justifying Harvey’s

heretofore unawarded status as an auteur.

The crux of

Harvey’s films lies, of all places, within the title of Noel Coward’s most

beloved play: Private Lives. The private

sphere is sacrosanct in the filmic worlds that Harvey fashions, because the

self-determined fragmentation and moderation of human behavior seems to

fascinate Harvey as his characters slingshot between public and private. This is most prevalent in Harvey’s films in

which his characters specifically operate as public figures, namely King Henry

II and Eleanor of Aquitaine in The Lion

in Winter (1968), the pseudo Sherlock Holmes and his crafty female

psychoanalyst Watson in They Might Be

Giants (1971), Queen Kristina of Sweden and Cardinal Azzolino in The Abdication (1974), Aimee Semple

McPherson in The Disappearance of Aimee

(1976), the two Wimbledon-class tennis pros in Players (1979) and the eponymous stroke-plagued actress in The Patricia Neal Story (1981). While these films especially function within

this construct, most of his other films also are suffused with this conceit as

well. Harvey’s gravitation towards material like

Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie (1973)

and Frederic Raphael’s Richard’s Things (1980),

despite their exclusive resignation to depicting the lives of ordinary people,

is still logical, particularly in the latter case. Both of these are about private lives and,

more aptly, inner lives. Grace Quigley (1985) takes an almost

farcical and darkly zany approach to charting the lives of the same brand of

ordinary people. The only anomalies

within this paradigm, Dutchman (1967)

and Eagle’s Wing (1979) use the

public sphere exclusively as a fisticuffs ring in which characters attempt to

resolve their private angst and interpersonal treachery. It is an unwilling stage platform for these

private lives. Put another way, the narratives

of these two films solely occur within the public sphere as to define Harvey’s

task as director as one being meant to show how private hostitilies disrupt and

irrevocably alter this public sphere.

Considering this

and other elements, one can perceive a voice and a preoccupation with certain

themes through which one can stake a claim for Harvey as an auteur. Add to this a richness of craftsmanship. The technicians and writers with whom Harvey

associated constitutes a formidable list of masters. Cinematographers Gerry Turpin, Douglas

Slocombe, Geoffrey Unsworth, Freddie Young, Billy Williams and Larry Pizer, and

writers Amiri Baraka (nee LeRoi Jones), James Goldman, Ruth Wolff, John Briley

and Frederic Raphael have all worked under the aegis of Anthony Harvey the

director. This is to speak nothing of

the impressive working relationships that had been sustained by Anthony Harvey

the editor. Though not an overt visual

stylist, save for Geoffrey Unsworth’s soft-focus work in The Abdication and Billy Williams’ epically charioscuro panoramica

in Eagle’s Wing, Harvey always

remained apt at subtle visual cues and framing a story within a larger visual

context using these cues.

Anthony Harvey’s

directorial debut Dutchman (1967) is Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? with the

braying, ornery uglieness turned up to eleven, featuring a young interracial

Taylor and Burton grappling for control over each other in an unmistakably

public arena, with the innocent bystanders as witnesses to the treachery and as

silent victims to the drama. Likewise

adapted from a stage play, the film is set in the underground New York City of

a subway train that doesn’t seem to me making its stops. An aggressive and obnoxious firecracker of a

woman named Lula takes a seat beside a young black man named Clay. Harvey tempers the early scenes with a

reactive but articulated zoom lens. In

an early shot preceding the meeting of the two characters, Harvey and his

cameraman Gerry Turpin choreograph a low-angle zoom from the foregrounded Clay

to the backgrounded Lula. With the

arrival of subway passenger onlookers in the second act, the zoom lens not only

ceases being reactive but ceases all usage en toto. The surrounding eyes that have congregated

take the place of these early reactive zooms, thus the camera approach changes, marks the point in which the film’s subjectivity switches and

turns on itself. It is a fascinating

stylistic choice. Although the film

certainly has weaknesses (for one, it is often too obvious in its roots as a

dated polemic on race), its virtue lies in this kind of sophistication.

In a quantum

stylistic leap from Dutchman, Harvey

moved on to his sophomore effort The Lion

in Winter, a well-budgeted and handsomely mounted Joseph E. Levine

production adapted from James Goldman Broadway stage play. The story involves King Henry II’s selection

of an heir to the throne, and Eleanor of Aquitaine’s struggle for influence in

the selection. Harvey’s latitude with

thematic auteurship is, of course, dictated by his treatment of the source

material, to which he is slavishly faithful.

The playwright James Goldman is also the film’s screenwriter. At heart, the play’s and the film’s central

idea of a human, character-driven insight into historical incident that almost

accidentally seemed to conform with Harvey’s past and future works. Peter O'Toole championed Harvey as director of the project from the outset. It was he who lured Hepburn to the co-starring role following rumors that she would retire after Spencer Tracy's death (the two of them had just co-starred in Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, for which Hepburn also won a Oscar statuette). Hepburn saw Dutchman at O'Toole's behest, fell in love with it, stating the film "grabbed you by the throat, which is exactly the approach that our material needed. Not that glossy old

MGM stuff, but cold people living in cold castles." She remained steady friends with Harvey for the rest of her life, as Hepburn would go on to star in two future Harvey productions, The Glass Menagerie (1973) and Grace Quigley (a.k.a. The Ultimate Solution of Grace Quigley) (1985).

Staging is of the essence in The Lion in Winter, even more so than its stage incarnation could have been. Looking at the film as an ensemble piece, every room in its castle location could be considered a smaller theater within the castle's (and the film's) larger theater. The perfect example to cite is the key scene that intimates a scandalous sexual relationship between Richard the Lionheart (Anthony Hopkins in his second film role) and King Phillip II (the debuting Timothy Dalton). As the two men are about to illicitly liaise, O'Toole's Henry II intrudes, prompting Richard to hide behind a nearby curtain. Richard becomes voyeur to a conversation between Henry and Phillip. The contrasts of the initial intimacy, the interruption of that intimacy, and the ensuing voyeurism all speak to Harvey as one who moderates and mines the levels of complexity in a favorite theme with taste and precision, even at such an early stage of his career as director, as if he knew the thematic path he would tread later.

As in Fred Zinnemann's A Man for All Seasons (1966) and Peter Glenville's Becket (1964, in which O'Toole plays the same character as in Lion), while the fate of a nation hangs in the balance within the film's narrative, the focus is not lavished on cold, impersonal epic pomp that would have plagued a more Samuel Bronston-esque production, but more on the contentious interpersonal power plays which determine that fate; how the private effects and conclusively transforms the public, for once and for all. We cannot see the latter morph, because Harvey nestles his interests in the former, but The Lion in Winter thus becomes a different kind of affair than A Man for All Seasons and Beckett, because Harvey is more specific in his approach and execution as to what it is about the narrative that engages him, and you can start to see this in the broader expanse of his work. Periodic scenes feature all of the characters together in the same space, but they will once again resign themselves to one-on-one hideouts in the same larger space. This is carefully schemed and choreographed, of course, by the writer, but it is orchestrated by its director. This is a key differentiating factor. Harvey's auteurship emerges in his representation of the reciprocity of his binary spatial constructions.

Excepting Mike Nichols' Carnal Knowledge, The Lion in Winter proved the last successful prestige production that Joseph E. Levine’s now-defunct Avco-Embassy Pictures mounted. In yet another quantum leap, Harvey followed up The Lion in Winter with a ripping yarn of a nutty comedy called They Might Be Giants, starring George C. Scott and Joanne Woodward, and produced by Paul Newman. It is in this film that an opening-up of Harvey's thematic thread of public vs. private occurs. The film tells the story of a widowed Manhattan lawyer named Justin Playfair who, in an apparent bit of paranoid delusion, believes himself to be Sherlock Holmes. He garbs himself in deerslayer attire and takes to the streets in search of his nemesis, Moriarty. His concerned brother hires female psychoanalyst Dr. Mildred Watson to treat him. Soon, largely thanks to her fortuitous surname, she is drawn into his infectiously exciting world of "adventure, danger and intrigue" against her better judgment. As Holmes/Playfair also lures a cast of “Bleecker Street irregulars” into his fantasy world, it becomes more and more apparent that these irregulars not just inhabit this world, but own it as well. The They Might Be Giants universe is one based in fanciful quixotic fable, where public and private become blurred, ultimately indistinguishable. If The Lion in Winter is about the existence of the binary of public and private, They Might Be Giants is about the deconstruction of that binary, and what happens when the barrier is torn away. Finally, at the final fade-out, it asks the existential question common and popular in the theater of the absurd: Does it matter to which reality we subscribe? The film, quite befittingly, has become a cult favorite over the years, even though its original box-office returns were somewhat less than encouraging (despite Maltin's description of it as a "box office disaster," which simply is hyperbole).

The Abdication, adapted from a stage

play by British dramatist Ruth Wolff, feels like a even more stage-bound work

than The Lion in Winter, sporting

flashbacks that were perhaps better served on stage, where its lead characters

more likely recounted strictly in words what the film version perfunctorily

stages in rather bland terms via recreated event. Pauline Kael, that imperious New Yorker dame, attacked the film, writing that the film is "embalmed in such reverence for its own cultural elevation that it loses all contact with the audience." Laying into Harvey, she continued, "Anthony Harvey directed, on his knees. We're never allowed to forget the

exalted rank of the characters, and nothing like human speech intrudes

upon the relentless dignity of Ruth Wolff's script." The rest of the reviews were not much better. The

Abdication and the television film The

Disappearance of Aimee are both rather dry treatments of their historical

sources. Only Geoffrey Unsworth’s

alluring but woefully ornamental soft-focus camerawork lifts it one step above. The nadir of Harvey's career came in the form of Players (1979), a Robert Evans pet-project for which the ex-Paramount head personally oversaw the making and marketing. Starring Evans' ex-wife, Ali MacGraw, as a tennis pro at Wimbledon in love with another player, Dean Paul Martin, a real-life tennis pro in a dreadful performance. However, disregarding the quality of the film, Harvey's burgeoning attraction to examining the dichotomy of public in relation to private is still palpable. Even in the most de rigueur work, Harvey lets this preoccupation be known, flashing it well above surface.

Harvey returned to form with two consecutive works: the exquisite Eagle's Wing (1979) and Richard's Things (1980). In the same tradition as Dutchman, Eagle's Wing showcases a string of characters engaged in a dedicated private struggle in the open public space, in this case the landscapes of American Southwest (versus the earlier film's single subway location). Eagle's Wing, penned by John Briley (Gandhi), is perhaps an apotheosis for Harvey as director probing specific and sustained thematics, and Richard's Things in response is his striking, calculated and effective diminuendo. It is also Harvey's return to the British film industry after a short tenure in Hollywood and American television films. The "public" in Eagle's Wing, however, is one that is of questionable basis. Harvey is constantly aware of this particular land as sacred space, and the film plays out visually, mostly silent, with a scant dependence on the spoken word, as not to disturb the gravitas in the vistas that Billy Williams' camera constructs. These vistas are not there simply to provide picture-postcard snap, crackle and pop. This is a film about the very meaning of land, meaning dependent on through whose eyes we choose to perceive it. Apotheosis, then, becomes the most apropos term. Public and private are again blurred, albeit in a way that is worlds away from the way it is blurred in They Might Be Giants.

At one point in the film, in a microcosm sequence, Martin Sheen's character Pike invades what can be nothing other than a sanctified space during the foiled ritual slaughter of the white horse that gives the film its title. The encounter ends in the accidental death of the Indian priest, followed by Pike's appropriation of the beautiful "mystical steed" that has been spared ritual death. The film becomes about something else: how the now-blurred public and private space has relative meaning. In a film that purports to be about "the West before the myths were born," what is not intimated is that the myths to which this opening voice-over alludes are myths manufactured by the white man. Eagle's Wing exists in what the civilized "white man" would call the primordial world, in an environment that naturally exists apart from the empty meanings it would be ascribed later in time. The horse is used by the white man to traverse the space. In this scene, it is intimated that the horse itself assumes ritual and spiritual meaning beyond the practical use the white man attributes to it. The ensuing duel between warrior White Bull (Sam Waterston) and fur-trapper Pike (Martin Sheen) quickly and unpretentiously ascends to the level of allegory, as two men grapple for dominion over the white horse Eagle's Wing. In a four-way struggle, with a posse recruited from a nearby hacienda in hot pursuit, the wide-open spaces of Eagle's Wing also allude to those who attempt to lend to the land a colonial (read: Christian) spirituality. For instance, at one point, White Bull traps a scorpion first with a tribal object decorated with feathers and beads, then exchanges it for a large crucifix-topped chalice-cover pilfered from a hacienda-bound stagecoach he ambushed earlier.

I am personally rather partial toward Tom Milne's review of the film in Time Out London: "Set in the as yet untamed American wilderness 'long before the myths',

this is unusual not only as a first-class Western made by a British

director, but in being virtually a silent movie as an Indian and a white

man (Waterston and Sheen), each a failure in his own world and

determined to prove otherwise, pursue a strange, obsessive duel for

possession of the glorious white stallion that gives the film its title.

Quirkishly funny as the duel evolves into a sort of medieval quest

attended by its own rituals and chivalries, the film gradually weaves

its concentric subplots (various other parties tag along behind, driven

by their own passions) into a plaintively spiraling lament for lost

illusions. Marvelously shot by Billy Williams, it's weird, hypnotic and magical."

The phrase "long before the myths" to which Milne alludes helps to introduce the film in the film's laconic "mysterioso" opening voice-over narration. It is one of the few films that examine the primordial, "pre-historic" West that ends with a tearful white man in defeat. As White Bull blazes off into a wide-open plain, trailing thick white dust behind him, Pike overlooks the victor's escape from a see-all vantage point and mournfully whimpers, "Help me...please...help me." It is a fitting way to end what is Harvey's best film, and what French cineastes might call his "testament film" (the one-film summation of a director's technique, the work that signifies "what cinema means" to that director). All the more extraordinary is the fact that it stands as Harvey's best not just because it clearly exemplifies everything he had been working towards throughout his entire directorial career, but also because of a clarity and poetic truth inherent in the final product. The film has only recently been released to video in its original anamorphic widescreen form. Eagle's Wing and The Lion in Winter mark the only occasions Harvey uses this format, usually reserved for large-scale productions. In the case of the former of the two, the film loses its very soul when it is reformatted to fit the standard television screen. It becomes an emptier work, less about the land, the mythics, the allegory, et al. than the chase itself (or what is left to see of it).

In another in a series of film-to-film departures, Richard's Things is based on a novel and a screenplay by Frederic Raphael, author of John Schlesinger's Darling (1965) and Far From the Madding Crowd (1967), Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut (1999) and the BBC miniseries "The Glittering Prizes" (1976), also based on his own novel. While I would certainly argue that his best, most accomplished work on both an aesthetic level and storytelling level remains Eagle's Wing, Richard's Things is likewise one of his richest works, and one that stands up next to the likes of The Lion in Winter and They Might Be Giants, despite dissent from shallow critics who have listlessly reduced it to an insipid, facile stereotype which unjustly cheapens the work. Harvey's drama, featuring Liv Ullmann (yet another Harvey alumnus from her work in The Abdication) in a colossally challenging lead role which won her the Best Actress prize at the Venice Film Festival, can easily be and has been lazily displaced into the "average lesbian soap opera" camp. Andrew Sarris, scholar and Village Voice critic of the time, was among the few to note its subtle power, writing, "I am hopelessly hooked on the scintillating blend of sensuality and sensibility expressed through the intense rapport of Liv Ullmann and Amanda Redman. Oh those lips and those eyes. Ullmann has never acted as eloquently and emotionally in English. Magic is worth celebrating."

The film tells the story of Kate Morris (Ullmann) who, following twenty years of marriage, is confronted with the news of her husband's death while he is away on a business trip. His hotel register reveals that he had been traveling with another woman. Kate tracks her down her rival and discovers the secrets of her husband's double life. However, as the two women talk about their relationship with Richard, this becomes a kind of exorcism for both of them. This soon develops into a physical relationship between the two women. Where Eagle's Wing filled its canvas with breathtaking visuals and largely dialogue-free sound design, Richard's Things conversely fills its canvas with the motion picture equivalent of "the talking cure," i.e. scenes that are driven by mutual psychoanalysis and a kind of symbiotic therapy between the two women. The film's cinematographer, however, is Freddie Young, who lensed expansively epic productions like Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, Nicholas and Alexandra, and many others. Young is no stranger to dialogue-driven films that function often like stage plays, including Robert Enders' Stevie (1978), starring Glenda Jackson. Superficially, the film sounds Bergmanesque: a brooding, Persona-like two-women study of an interpersonal communion born from an infidelity -- what Susan Sontag called "the violence of spirit" when she described the theme of Persona.

The level of sophistication of Richard's Things easily usurps films like Robert Towne's Personal Best (1982), although Georges Delerue's score sometimes threatens to suffocate that sophistication. In tone, the film tends to feel like a cousin to Schlesinger's Sunday, Bloody Sunday (1971), which is fitting for many reasons. The main reason is the respective sensitivity of both works, which computes because both Schlesinger and Harvey were/are gay men. What makes the central romantic relationship between the two women particularly fascinating in Richard's Things is that the erotic is given rise through a kind of exorcism, i.e. drudging up an inner-private life and making it public to another. The question is not one of space, as it had been in Eagle's Wing. The world of spaces in Richard's Things is almost entirely private, although a key scene in a supermarket early in the film, in which the cuckolded Ullmann slips an incriminating personal item into her rival-cum-lover's shopping basket may momentarily say otherwise. On the whole, however, the idea of public vs. private becomes more of an abstraction in the film, but not any less of a thematic presence. Ullmann's last words in the film, in a voice-over monologue, allude to public illusion and presentation. As she drives off into an uncertain future, having left behind her new lover, we leave in the film exactly how we first encounter her, in the driver's seat of a car as she she says, "My pleasure will come from being what people believe me to be, and from not quite being it. I shall never be suspected of being other than what I appear, and I shall appear to be exactly what I am." This deceit is pure Anthony Harvey -- a signature.

Grace Quigley (1985) started as a script by A. Martin Zweiback, entitled The Ultimate Solution of Grace Quigley. It had been a pet project of Hepburn's for eleven years when Golan and Globus of Cannon Films agreed to finance it, and Harvey agreed once again to stand at her side as director. Featuring Nick Nolte as a beleaguered hit man faced with the prospect of administering euthanasia for pay, the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1984 at 102 minutes to the most dismal of notices. Originally slated to play in-competition at the festival, its cold reception from the programming committee relegated it to an out-of-competition slot. The film was twice re-edited, at 87 and 94-minute versions, once even by Zweiback the screenwriter, respectively all with different endings. Theatrically released in the U.S. one whole year later in May 1985, the film came and went without a whisper. It was Katharine Hepburn's final leading role in a motion picture. The film's troubled post-production speaks to the fact that it is a troubling (but nonetheless interesting) film.

Tonally, Grace Quigley defies Harvey's other works, even that of the wild and woolly They Might Be Giants. It takes the anarchy of that earlier film to another level. The characters on Nolte's mercy-kill list are fond of gathering for what could only be described as "death parties," where they air their joy at the prospect of facing the eternal void, making it well known how miserable their lives are. I have only seen the Cannon-approved cut of this film. Curiously, Maltin pans this version, calling it an "abysmal misfire that manages to be both bland and tasteless," yet in the same review calls the 94-minute director's cut of the film "a touching, funny and surreal black comedy about the problems of the elderly and the right of choice." It goes to show you what a little editing can do! I have not seen the version with the better review, so I refrain from extensive commentary on this title until I can get around to scoring a copy.

Although Harvey is still alive (at the time this article is being written, he will be 82 years old in June), but Grace Quigley proved to be his final theatrically released film, and he has long since ceased working as a filmmaker. He officially ended his career with the television film This Can't Be Love (1994), once again starring Katharine Hepburn, this time paired with Anthony Quinn. I have not seen This Can't Be Love. His career, however, is that whose auteurship is specific and honed in a sustained focus. I find myself continually frustrated by directors who are overwritten-about, whose claims to auteurship are, in reality, based on precious little to make the claim for them, apart from occasional, isolated "good work" without the threads and through-lines to the rest of the director's work. Go back to the source. Andrew Sarris defined auteurship and auteur theory as "the idea that a director helps shape the creative intent of a film." From The Lion in Winter through Richard's Things, from They Might Be Giants through Eagle's Wing, Harvey has often made films that are worlds apart from each other, but has clearly demonstrated how authorship and voice can emerge from any genre that exists within a director's corpus.

At one point in the film, in a microcosm sequence, Martin Sheen's character Pike invades what can be nothing other than a sanctified space during the foiled ritual slaughter of the white horse that gives the film its title. The encounter ends in the accidental death of the Indian priest, followed by Pike's appropriation of the beautiful "mystical steed" that has been spared ritual death. The film becomes about something else: how the now-blurred public and private space has relative meaning. In a film that purports to be about "the West before the myths were born," what is not intimated is that the myths to which this opening voice-over alludes are myths manufactured by the white man. Eagle's Wing exists in what the civilized "white man" would call the primordial world, in an environment that naturally exists apart from the empty meanings it would be ascribed later in time. The horse is used by the white man to traverse the space. In this scene, it is intimated that the horse itself assumes ritual and spiritual meaning beyond the practical use the white man attributes to it. The ensuing duel between warrior White Bull (Sam Waterston) and fur-trapper Pike (Martin Sheen) quickly and unpretentiously ascends to the level of allegory, as two men grapple for dominion over the white horse Eagle's Wing. In a four-way struggle, with a posse recruited from a nearby hacienda in hot pursuit, the wide-open spaces of Eagle's Wing also allude to those who attempt to lend to the land a colonial (read: Christian) spirituality. For instance, at one point, White Bull traps a scorpion first with a tribal object decorated with feathers and beads, then exchanges it for a large crucifix-topped chalice-cover pilfered from a hacienda-bound stagecoach he ambushed earlier.

The phrase "long before the myths" to which Milne alludes helps to introduce the film in the film's laconic "mysterioso" opening voice-over narration. It is one of the few films that examine the primordial, "pre-historic" West that ends with a tearful white man in defeat. As White Bull blazes off into a wide-open plain, trailing thick white dust behind him, Pike overlooks the victor's escape from a see-all vantage point and mournfully whimpers, "Help me...please...help me." It is a fitting way to end what is Harvey's best film, and what French cineastes might call his "testament film" (the one-film summation of a director's technique, the work that signifies "what cinema means" to that director). All the more extraordinary is the fact that it stands as Harvey's best not just because it clearly exemplifies everything he had been working towards throughout his entire directorial career, but also because of a clarity and poetic truth inherent in the final product. The film has only recently been released to video in its original anamorphic widescreen form. Eagle's Wing and The Lion in Winter mark the only occasions Harvey uses this format, usually reserved for large-scale productions. In the case of the former of the two, the film loses its very soul when it is reformatted to fit the standard television screen. It becomes an emptier work, less about the land, the mythics, the allegory, et al. than the chase itself (or what is left to see of it).

In another in a series of film-to-film departures, Richard's Things is based on a novel and a screenplay by Frederic Raphael, author of John Schlesinger's Darling (1965) and Far From the Madding Crowd (1967), Kubrick's Eyes Wide Shut (1999) and the BBC miniseries "The Glittering Prizes" (1976), also based on his own novel. While I would certainly argue that his best, most accomplished work on both an aesthetic level and storytelling level remains Eagle's Wing, Richard's Things is likewise one of his richest works, and one that stands up next to the likes of The Lion in Winter and They Might Be Giants, despite dissent from shallow critics who have listlessly reduced it to an insipid, facile stereotype which unjustly cheapens the work. Harvey's drama, featuring Liv Ullmann (yet another Harvey alumnus from her work in The Abdication) in a colossally challenging lead role which won her the Best Actress prize at the Venice Film Festival, can easily be and has been lazily displaced into the "average lesbian soap opera" camp. Andrew Sarris, scholar and Village Voice critic of the time, was among the few to note its subtle power, writing, "I am hopelessly hooked on the scintillating blend of sensuality and sensibility expressed through the intense rapport of Liv Ullmann and Amanda Redman. Oh those lips and those eyes. Ullmann has never acted as eloquently and emotionally in English. Magic is worth celebrating."

The film tells the story of Kate Morris (Ullmann) who, following twenty years of marriage, is confronted with the news of her husband's death while he is away on a business trip. His hotel register reveals that he had been traveling with another woman. Kate tracks her down her rival and discovers the secrets of her husband's double life. However, as the two women talk about their relationship with Richard, this becomes a kind of exorcism for both of them. This soon develops into a physical relationship between the two women. Where Eagle's Wing filled its canvas with breathtaking visuals and largely dialogue-free sound design, Richard's Things conversely fills its canvas with the motion picture equivalent of "the talking cure," i.e. scenes that are driven by mutual psychoanalysis and a kind of symbiotic therapy between the two women. The film's cinematographer, however, is Freddie Young, who lensed expansively epic productions like Lawrence of Arabia, Doctor Zhivago, Nicholas and Alexandra, and many others. Young is no stranger to dialogue-driven films that function often like stage plays, including Robert Enders' Stevie (1978), starring Glenda Jackson. Superficially, the film sounds Bergmanesque: a brooding, Persona-like two-women study of an interpersonal communion born from an infidelity -- what Susan Sontag called "the violence of spirit" when she described the theme of Persona.

The level of sophistication of Richard's Things easily usurps films like Robert Towne's Personal Best (1982), although Georges Delerue's score sometimes threatens to suffocate that sophistication. In tone, the film tends to feel like a cousin to Schlesinger's Sunday, Bloody Sunday (1971), which is fitting for many reasons. The main reason is the respective sensitivity of both works, which computes because both Schlesinger and Harvey were/are gay men. What makes the central romantic relationship between the two women particularly fascinating in Richard's Things is that the erotic is given rise through a kind of exorcism, i.e. drudging up an inner-private life and making it public to another. The question is not one of space, as it had been in Eagle's Wing. The world of spaces in Richard's Things is almost entirely private, although a key scene in a supermarket early in the film, in which the cuckolded Ullmann slips an incriminating personal item into her rival-cum-lover's shopping basket may momentarily say otherwise. On the whole, however, the idea of public vs. private becomes more of an abstraction in the film, but not any less of a thematic presence. Ullmann's last words in the film, in a voice-over monologue, allude to public illusion and presentation. As she drives off into an uncertain future, having left behind her new lover, we leave in the film exactly how we first encounter her, in the driver's seat of a car as she she says, "My pleasure will come from being what people believe me to be, and from not quite being it. I shall never be suspected of being other than what I appear, and I shall appear to be exactly what I am." This deceit is pure Anthony Harvey -- a signature.

Grace Quigley (1985) started as a script by A. Martin Zweiback, entitled The Ultimate Solution of Grace Quigley. It had been a pet project of Hepburn's for eleven years when Golan and Globus of Cannon Films agreed to finance it, and Harvey agreed once again to stand at her side as director. Featuring Nick Nolte as a beleaguered hit man faced with the prospect of administering euthanasia for pay, the film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in May 1984 at 102 minutes to the most dismal of notices. Originally slated to play in-competition at the festival, its cold reception from the programming committee relegated it to an out-of-competition slot. The film was twice re-edited, at 87 and 94-minute versions, once even by Zweiback the screenwriter, respectively all with different endings. Theatrically released in the U.S. one whole year later in May 1985, the film came and went without a whisper. It was Katharine Hepburn's final leading role in a motion picture. The film's troubled post-production speaks to the fact that it is a troubling (but nonetheless interesting) film.

Tonally, Grace Quigley defies Harvey's other works, even that of the wild and woolly They Might Be Giants. It takes the anarchy of that earlier film to another level. The characters on Nolte's mercy-kill list are fond of gathering for what could only be described as "death parties," where they air their joy at the prospect of facing the eternal void, making it well known how miserable their lives are. I have only seen the Cannon-approved cut of this film. Curiously, Maltin pans this version, calling it an "abysmal misfire that manages to be both bland and tasteless," yet in the same review calls the 94-minute director's cut of the film "a touching, funny and surreal black comedy about the problems of the elderly and the right of choice." It goes to show you what a little editing can do! I have not seen the version with the better review, so I refrain from extensive commentary on this title until I can get around to scoring a copy.

Although Harvey is still alive (at the time this article is being written, he will be 82 years old in June), but Grace Quigley proved to be his final theatrically released film, and he has long since ceased working as a filmmaker. He officially ended his career with the television film This Can't Be Love (1994), once again starring Katharine Hepburn, this time paired with Anthony Quinn. I have not seen This Can't Be Love. His career, however, is that whose auteurship is specific and honed in a sustained focus. I find myself continually frustrated by directors who are overwritten-about, whose claims to auteurship are, in reality, based on precious little to make the claim for them, apart from occasional, isolated "good work" without the threads and through-lines to the rest of the director's work. Go back to the source. Andrew Sarris defined auteurship and auteur theory as "the idea that a director helps shape the creative intent of a film." From The Lion in Winter through Richard's Things, from They Might Be Giants through Eagle's Wing, Harvey has often made films that are worlds apart from each other, but has clearly demonstrated how authorship and voice can emerge from any genre that exists within a director's corpus.

.png)